How Long Does It Take To Become A Doctor?

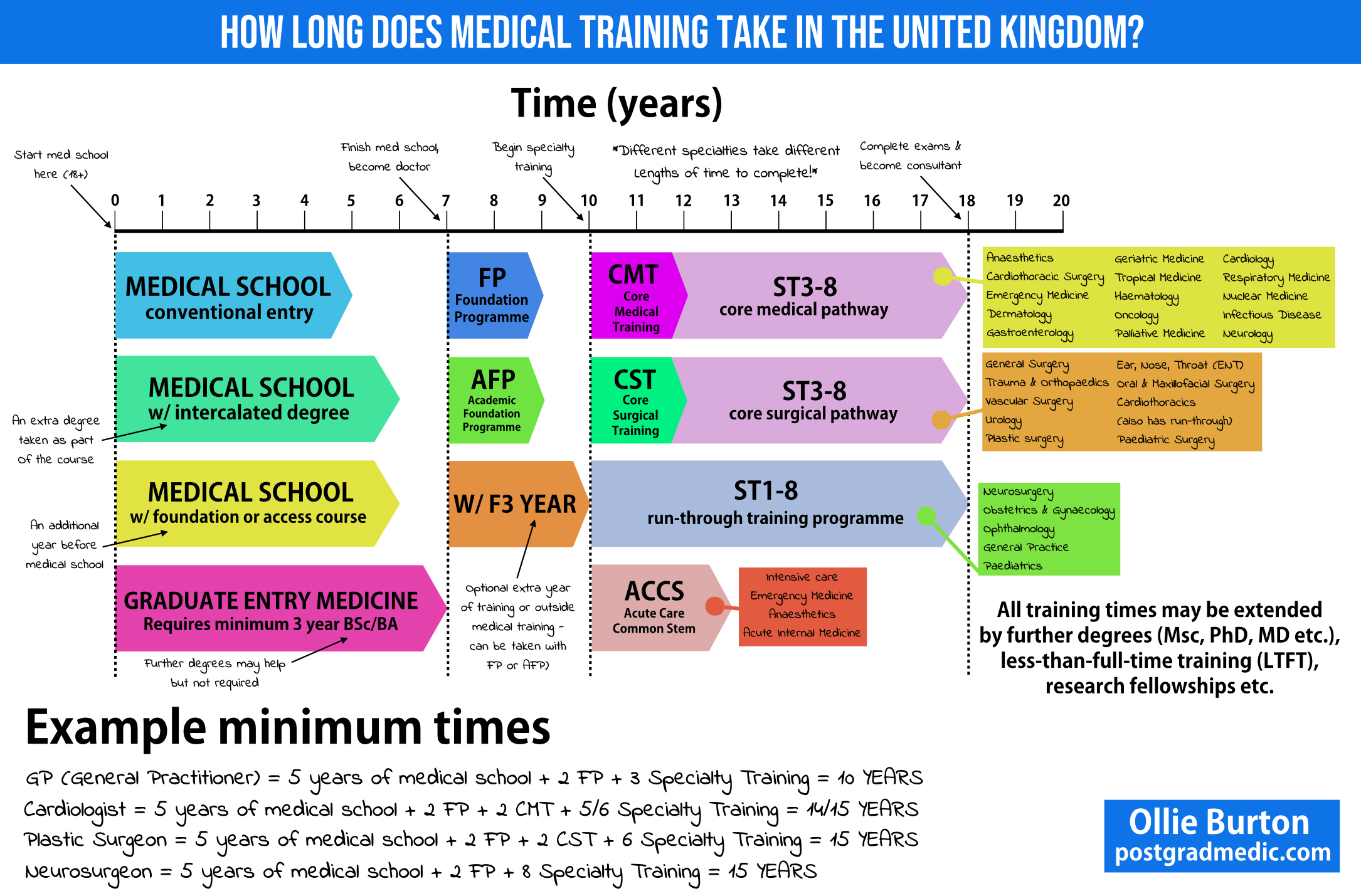

I get asked all the time, especially by friends and family - just how long are you going to be at medical school? It’s something all us medical students need to think about before we start, but even having done a lot of research before I applied, there was still left to learn that I’ve picked up since getting here. I’ve put together an infographic that illustrates the broader guidelines.

Right then, standard entry to medicine. You go when you’re 18 after completing your A levels, entering into first year, and these courses are usually 5 years long. That means you’ll enter at 18 and finish at 23. Some UK schools have an optional or compulsory intercalated degree year for a Bachelor’s or Masters, which would add another year for a total of 6. This would be the same if you completed a Foundation or Access to Medicine course too. Then there’s graduate entry medicine, which requires at the very least an undergraduate degree to complete, which is a 3 year investment. However the tradeoff here is that you essentially get to skip a year of the course due to the content being compressed, which makes it 7 years long.

Congratulations, you’ve finished medical school and passed your final exams. You are now able to call yourself Doctor with some letters after your name such as MBBS or MBChB - they’re all equivalent, don’t worry. This is the point at which you start earning money. You then have to complete 2 years of Foundation Training as a junior doctor - in the first year you have a provisional license to practise medicine, with the full license for unsupervised practice being obtained after that first year and then you complete the second year of training with that license. During each of these years you’ll rotate between various specialties and gain a basic set of core competencies.

You can also apply for the Academic Foundation Programme instead, which takes the same amount of time but gives you some protected research time you can spend working on an academic research project or in an educational setting, for example. Some people also choose to take an extra year out here as F3, either to have a break from training or pursue other projects, teach or maybe to get themselves ready for specialty training.

At this point you then need to decide what specialty you want to do and things get a bit more complex! Let’s start simple and say you want to become a General Practitioner - this is currently the shortest training pathway and takes 3 years after completing foundation training, meaning your total medical school journey, assuming you started at 18 in the conventional pathway is 10 years long.

Let’s say you want to be a cardiologist - you’ll need to spend another two years in Core Medical Training, CT1 and CT2, which almost all medical doctors will do. After that, you then apply to go into specialty training specific to cardiology and enter at the ST3 level, or Specialty Training 3, your 3rd year after foundation. You then stay on this programme and go through four more years to ST7, with the option of a final ST8 year to subspecialise and then become a full, bona fide consultant. While you’re in specialty training you are known as a specialty registrar, which is still technically a junior doctor.

Let’s now give a surgical example - you now want to be a orthopedic surgeon. Similar to medical programmes, you need 2 years of core surgical training, CST1 and CST2, which almost all surgeons will do. After that it’s 6 years of specialty training, agains starting at ST3 and ending at ST8 as a consultant surgeon. The other major pathway after foundation training is run-through specialty training programmes. This means that instead of having to do core training and learning the basics that overlap with other specialties, you focus on the end goal right from the start and only do training relevant to that job. A good example is neurosurgery, where instead of CST1 and 2, you begin right away at ST1 and go right through to ST8. There are advantages and disadvantages to this - there is only competitive step, entry to ST1, so once you’ve got your foot in the door you’re sorted until the end. Obviously if you change your mind it’s a lot more difficult to change direction because you have not done the core training which would allow you to enter a different specialty later.

The last pathway we’re going to discuss here is ACCS - the acute care common stem training programme. This pathway focuses as the name suggests on four acute care parent specialties - intensive care, emergency medicine, acute internal medicine and anaesthetics. This pathway takes 3 years to complete, and allows you to undertake higher training in those parent specialties. Anaesthetics for example also has its own core medical training programme, so be sure to look more at CMT and ACCS if that’s something you’re interested in.

So that’s a very quick overview of higher medical training through junior and senior ranks. We said earlier for a GP you’re looking at 10 years minimum investment. For most others it’s another 5 years on top of that - you could go in at 18 and be 33 as a consultant. Of course that assumes you don’t do anything else, like Masters Degrees, PhDs/MDs, research fellowships, teaching placements etc which would extend it further.

The Pros and Cons of Graduate Entry Medicine

While undergraduate courses are seen as the 'standard' entry route into medicine, graduate-focused programmes are responsible for producing a huge number of doctors, and may offer a better deal for applicants who already hold degrees.

Pro: Saving a Year

Let’s start with an obvious one. Graduate entry programmes allow you to complete a medical degree in four years rather than five, which is obviously a good thing if you’re eager to get into practicing as a doctor. If you didn’t make the grades first time around for example, you could complete an undergraduate degree by 21, and then graduate as a doctor at 25, only two years behind those that started at 18, with all the extra experience and opportunities to boot.

Con: Losing a Year

Of course, this also has its downsides. Medicine has a reputation for being an incredibly challenging degree, and graduate schemes cram the already huge amounts of material into a shortened time frame. If you’ve been out of education for a while or are worried about finding the academic transition difficult, it might be worth considering five year courses to make your life just that little bit easier.

Pro: More maturity

On a similar note, because of the increased average age, your cohort should (at least in theory) be a bit more mature than a comparable cohort at 18 years old. Of course that’s not to suggest that undergrad-entry medical students are immature at all, but simply by virtue of being older people are more likely to be more collected and capable of managing their lives and social relationships properly.

Con: Money

This is probably more noticeable to those that have been employed in a real-world job, in that you absolutely will not be able to work while studying and your income will suffer as a result. In a similar vein to before, your friends will start to become established in their careers sooner than you, and basically you will be on low-income posts for a while even after graduation.

Pro: Funding is available!

Given the recent removal of the nursing bursary, I’m not sure how much longer this point will remain true, but for now at least a graduate-entry medical programme can be funded through Student Finance England. There’s a not-tiny sum that must be paid upfront (approximately £3375), after which a standard student loan is available to cover the rest.

Con: Qualifying Older

It seems like a stupidly obvious thing to say, but it’s worth thinking about. As of right now I’m 21 years old, so this won’t be as large a problem, but let’s take a reasonable guess and say that the average age on my course is around 25. It takes 4 years to complete the degree, which will make most people around 29/30 when starting work as an F1, a notoriously stressful and time-intensive role. By that point most people’s friends will be settled down and may have children, and if you have significant responsibilities or relationships of your own, a medical degree could be very disruptive. These things can definitely be managed properly, but it will make some elements of more life more difficult.

Pro: Wider Range of Backgrounds

Because graduate-entry courses demand a first degree as part of the application process, by necessity every single person on the course will have at least an undergraduate degree under their respective belts. While some schools will only accept science graduates, there a few (including Warwick where I go) that happily take arts and humanities students too. This leads to a fantastic array of knowledge and unique perspectives that serve the year very well as a whole, particularly when it comes to group work.

Con: Competition

Getting a place on a graduate entry scheme is rough. Competition is comparatively more fierce because everyone has more experience and knowledge than the typical school leaver. This leads to either the use of the GAMSAT (a 6 hour slog of an exam that tests your reasoning across humanities and natural sciences) or higher cutoffs in the UKCAT and BMAT. In 2013, for example, Warwick (one of the two grad-only medical schools) had close to 3000 applications for about 170 places. I did the maths, and for 2017 entry (considering only home applicants for undergraduate and postgraduate courses) at undergraduate level there were 9.2 applicants per place, with 25.8 applicants per place for graduate-entry courses.

You’ll get to be a doctor

But of course, the ultimate positive from a graduate-entry scheme is that at the end of it, you’ll get to be a doctor. That’s the ultimate reason why any of us that applied to study medicine did so, and regardless of whether you choose a four year or five year scheme, we’ll all be in it together doing what we set out to do.

How NOT to Choose A University

Just as there are many excellent ways to help you choose where you might want to study, there are a few that are abjectly, objectively terrible that I highly recommend you avoid.

1. League Tables

Let’s get this one out of the way first, league tables are a waste of mine, yours and everyone else’s time. They are inconsistent with each other, all use different metrics and the positions jump around so much year to year that you’d think these departments were in constant flux. This is obviously true to a very small extent given that staff and module content might change in their minutiae, but newspapers are writing them to sell newspapers and websites are writing them for clicks and ad revenue.

If you are going to insist on doing this, then just avoid choosing somewhere that’s right at the bottom of the list across multiple lists, but other than that I really don’t think it matters. Employers don’t care, I don’t care, and you shouldn’t care either. If you’ve found somewhere you want to go, then go there and don’t let anyone give you sh*t for it.

2. It’s close to home

This is admittedly a very tough one, and will be contentious - but ultimately it comes down to being somewhere where you can live away from home. I think that one of the great aspects of university living is that it gives you control and makes you responsible for your own life.

I went to Newcastle University, approximately 2-3 hours by car away from where I live, which was close enough for me that I could still get back urgently if necessary, but crucially still allowed me to shape my own existence. Being somewhere else, even if it’s just student accommodation, even for just the first year of the course is an experience that I think everyone should have.

In that time you’ll learn by necessity to cook, clean, socialise and fundamentally become a more rounded member of society (or at least in theory). This won’t be for everyone, and that’s perfectly fine, but living in the sheltered bubble of home will I think deprive you of certain things.

"Being somewhere else, even if it’s just student accommodation, even for just the first year of the course is an experience that I think everyone should have"

3. The Minimum Grade Offer

I will examine this topic in more depth in the future, but remember that the minimum UCAS or grade requirements for a course DO NOT indicate how good that course will be for you.

These requirements indicate two things at best: Firstly, they reflect how competitive entry is, because if they have a fixed number of places but a ton of applicants, they need to be more selective by definition and raising boundaries is a good way of eliminating a large number of people very quickly. Of course it does stand to reason that better courses will have more applicants, but that does not necessarily have to based on quality of teaching - there are more than likely a multitude of factors at play that warrant further investigation.

Secondly, universities are playing a game with the UCAS system that plays on the above point. Schools want to fill all their degree places because that means more money, so it is reasonable from their perspective to inflate the entry requirements. More students will then assume that it’s a better course, apply for it, subsequently fail to make the grades, but the university will take them anyway. It’s a devious game but it’s easy to see how unwilling students can be preyed upon like this.

4. Your Parents Said So

The absolute worst reason of all, and something I’ve noticed multiple times when giving tours of Newcastle. Your parents, while they love you very deeply and I have no doubt want the absolute best for you, do not share your mind. They do not know as well as you do where it is you want to go and study, and if you are not able to stand up to them and tell them that, realise that it’s probably a good indicator of worse problems to come later on in life.

This is usually a particular type of parent, and it can lead to uncomfortable standoffs, but it’s far better to get it out the way - I myself have taken parents aside while doing tours and tried to recommend that they back off and allow the student to ask me questions. In cases where it’s plainly obvious that the applicant doesn’t want to be here, I’ll tell them that too, and there is absolutely nothing wrong with that. Go where makes YOU happy, not your parents. If at all possible, go to open days without them, and then have a second visit with them in tow if you’re still interested.

How to Choose A University

Here in the United Kingdom there are currently more than a hundred universities, each of which represents a viable place to study for new applicants. In this article I'll go through a few ways you can narrow down your search in time for the UCAS deadlines.

Keble College, University of Oxford

1. What subject?

The first and potentially easiest way of choosing your university is deciding what you might like to study. Here’s an easy exercise - if you’re applying with A levels or some equivalent through UCAS, open up a spreadsheet in Excel, write down the names of some universities (choose them at random if needs be!) and see if each place on the list even offers the course you want. Mark down the grades you need at each school and then rinse and repeat for as many subjects as you want - this is a nicely organised way of working through it and will make it easier to compare your options.

You’ll normally find all the relevant information on the university website, such as the aforementioned grade requirements, details of the application process (entrance exams, interviews etc.) along with aspects of the course that might be specific to that school - this is a great means of learning more about what each institution offers and might entice you towards or even repel you away from a particular place. This sounds negative at first, but in both cases it makes the final considerations simpler.

2. The Russell Group

Listen, I am not (or at least would not like to think I was) an elitist when it comes to education - I was happily state-schooled, and I have met people from an enormous range of backgrounds in the academic sphere who were all fantastically competent. By and large, I do not think that whether a university is part of the Russell group should sway your decision.

However, in my opinion, if you are considering biology or chemistry I would perhaps let it play on your mind just a tad. My reasoning is this: In such a university, your lecturers are more likely to have their own academic research going on which will enhance your chances of extracurricular opportunities in this area (see point 4). I think there are sufficiently few people taking maths and physics courses at present that demand exceeds supply for competent graduates in these areas, but this does not appear to be true as a whole across the sciences.

This is very much a generalisation, and many people will disagree, but this goes for all subjects of study - if you think that academia as the endpoint could be what you desire, (or industry research for STEM fields), then I think I would be doing you a disservice by not at least suggesting that you look into this aspect.

The IGEM competition as of present is only entered by research-focused UK universities