Introduction to Applying to Medical School

Medical schools in the UK can vary greatly in their admissions processes, but there are several elements that hold true for the majority. This article is intended for those completely new to the process and who are considering their applications in the future.

1. Grades & Academic Achievement

For undergraduate entry, the minimum requirements to be attained are three A grades at A2. Biology is required virtually everywhere, and most schools demand a second science subject (Maths, Physics or Chemistry). If you wish to only take two sciences, Chemistry is currently the options sought by most schools. The third A level choice does not appear to be of any consequence for most places, so my advice would be simply to take something you will score well in.

If you are applying as a graduate who already holds a degree (or will graduate in the coming summer) usually a 2.1 (Upper Second Class Honours) in a science subject is optimal, although many schools will take graduates of any disciplines.

Note: It is vitally important to check the individual requirements of each university you apply to. This guide is intended as a rough primer only and cannot encompass the individual preferences of the schools.

Medicine offers a dynamic career with a range of opportunities (Image: RAF Lakenheath)

2. Entrance Exams

Of course, many students will achieve the grades as detailed above. The next criterion to tackle is the entrance exams required by the universities you’re applying to (these will be listed on the university website under Admissions/Applications). In most cases this will be the UKCAT (United Kingdom Clinical Aptitude Test) which must be booked at the UKCAT registration website and sat between July 3 and October 3. Alternatively some schools ask for the BMAT (BioMedical Admissions Test), which is similar and booked separately.

Note: The UKCAT is sat before the UCAS deadline for medicine (October 15), whereas the BMAT is usually sat afterwards in early November. This means that should your UKCAT exam not go as well as you’d hope, there might still be time to take the BMAT and apply to different schools.

3. UCAS Applications - Personal Statement & Reference

Whether you are applying as a school-leaver or as a graduate, all medical school applications are sent through the UCAS system (Universities and Colleges Admissions Service) - medicine is an undergraduate course, no matter the entry route. You’ll need to provide personal information, including previous academic attainment (GCSEs or similar) and any grades you have.

You will write a personal statement, no longer than 4000 characters. In brief, it should sum up your motivation for studying medicine, give an indication as to why you think you would be a suitable candidate and give some evidence that you’ve properly considered the reality of the career ahead of you. We’ll explore this in more depth another time.

You will also need to find someone willing to give you a reference - usually this will be someone from your college or sixth form, and potentially a university tutor if you’re a graduate. It would be best if they had previous experience of writing references for medicine, but if this is not feasible there is plenty of guidance online. Whether they share the details of this with you is entirely up to them, and it is sent separately through UCAS by your administrator.

"It is vitally important to check the individual requirements of

each university you apply to"

4. Work Experience / Volunteering

In keeping with the previous point, medicine is often idealised and glamourised by the media, which might not offer the best representation of the career. It is more than worth the time and effort to gain some healthcare-relevant work or volunteering experience, be it working in a nursing home, employment in a pharmacy or similar.

Once again the advice of each institution is highly variable, both in terms of the types of experience they consider suitable and whether it is required at all. This is particularly of concern for graduate applicants to medicine, and is more frequently used as a minimum threshold exercise at this level than for school leavers.

I worked with the Nightline group at Newcastle University, an anonymous support phoneline.

Picture: I was Neville The Bear for a recruitment day, the mascot of the service.

5. The Interview

If you’ve satisfied all the previous criteria and impressed the right person at the right time, you might find yourself the lucky recipient of an invitation to interview. You’ll be elated, as well you should be, as this is the final hurdle (beyond achieving your grades of course) to overcome before beginning your passage to medical school.

There are several types of interview employed by medical schools to pick the best candidates from the ones who have made it this far. Once more there will be another article to come detailing their differences, but essentially you will go to the university and speak to one or more people about why you deserve the place.

"Don’t be nervous and understand that interviewers are simply to trying to learn more about you"

Depending on the school you might be asked academic questions, about the contents of your reference/personal statement, aspects of the NHS, and other such markers that illustrate your suitability for medicine. Don’t be nervous and understand that interviewers are simply to trying to learn more about you, as you’ve previously only been a piece of paper and some ink up to that point. Medicine requires a large range of skills, including communication, which is one of the main ones being tested although it certainly won’t be the only one. If it goes well (fingers crossed!) you’ll hear back with an email offering you a place, and the real journey will begin.

So there is your primer to the medical admissions process, I hope you’ve found it useful and as usual I encourage you to ask me any questions if there’s something you’d like to know. I know all too well how stressful and mystifying it can seem at times, which is of course why this website exists at all. Good luck, and I’m sure you’ll make a great doctor one day.

Reflections from Newcastle: The Courier (Student Newspaper)

I’ve said at every opportunity that academics and classes are only the beginning of your university experience - what rounds out your time there and you as a whole are the other experiences, the people you meet and the things you do. Societies act as a catalyst for such experiences and are a fantastic way to make new friends doing what you love, or even trying something completely new.

There are three main elements to my experience with societies, two of which were particularly large time demands. What I mean to say by this is that while other people may have been regular attendees at more or fewer groups, this was the balance that worked out best for me alongside my other pursuits. I’ll be doing an article on each of these to analyse them separately.

The Courier

First and foremost is the university newspaper, The Courier. The way this works is that every week, the editors of each themed section of the paper meet with writers and assign articles or accept pitches from writers. For example, if a particular disease was prevalent in the media, or a large-scale political event such as the 2017 general election, you might be given a 500 word piece to write for next week’s issue.

I wrote mainly for the science and gaming sections, but did dabble elsewhere too. When second year came around I applied to be a science section editor, but there was a logistical mixup and it was assumed that I’d gone for gaming instead. While it wasn’t what I necessarily wanted at the time (and in truth was quite irritated), I went ahead and it turned out to be an amazing experience. That was how I met my two friends Michael and James who were my coeditors for the section, and we gelled really well.

"...I of course decided to stay on, and once again expressed interest in becoming a science editor. It was not to be however..."

So by this point we were the ones pitching the articles every week and laying it up in Adobe InDesign ready for the paper to be printed. Again it’s worth pointing out that this work is done in an office alongside all the editors from the other sections, such as Film, Music, Sport, Lifestyle, Arts, there’s so much work goes into each and every issue. Because you all have different interests but are working towards a common goal in a great looking weekly paper, everyone bonds well within the office and you really feel like part of a team. My favourite part of this year was the feature pages that we produced, in particular this Dark Souls one celebrating the launch of the third game in the series.

We were quite proud of this one.

When it came to my third year of studying, I of course decided to stay on, and once again expressed interest in becoming a science editor. It was not to be however, as the opportunity came around to become a deputy editor, which was a step up from where I was and involved looking at the paper on a more general level rather than being responsible for any one section. I’ll get there one day, damn it. It was at this point that I properly got to know my friends Jordan and Jared who went on to found the videogame journalism platform Quillstreak, and of course Errol who is one of the most perpetually busy people on the planet.

So in my last year I stepped back completely from pitching articles and influencing content, and everything became about consistent print layup between sections and helping the new subeditors with Photoshop and the ‘quirks’ of InDesign. This was also great because nothing cements your own knowledge quite like teaching, and you have to stop and think about why you’re doing what you are. It was a great way to get to know all the editors on a personal level too, perhaps even more than I did the previous year because of this particular aspect.

"When I was working with James and Michael we were lucky

enough to be awarded ‘Features of the Year'..."

Every year the students’ union hosts the Student Media Awards, which I attended in my second and third years - these were an absolute blast. There was way too much wine for too few people, but awards were given out to individuals from all aspects of the student media (including the radio and television stations), which is a fantastic way to honour those people that go above and beyond in providing a quality service.

When I was working with James and Michael we were lucky enough to be awarded ‘Features of the Year’, and at that same ceremony I gave a preamble speech before delivering an award to James Sproston, who was actually elected Editor for the paper for the 2017/8 academic year.

My first and last issues, along with the teams from both years

Working with The Courier has been an incredible experience, one that I never would have dreamed I’d have. I’ve never had aspirations to be a journalist at all, and genuinely still don’t, I’ve just found that I enjoy writing. The skills developed have helped me enormously even with my own coursework and essay crafting, and the layout principles have come in handy for academic posters.

I have in my possession pictures of the team from both years, and speaking quite personally they’re among the most valuable things I own in terms of sentimental value. I don’t know quite what it is but it’s been the closest thing to a family of people that I think I’ve experienced beyond my own because of that shared drive of so many wonderful and talented people, it’s really remarkable.

So whether you harbour an interest in tapping keys for a living or not, I cannot recommend that you get involved with your university paper enough. Beyond academics it’s been my favourite thing that I’ve done during my time at Newcastle, and despite not getting what I wanted at each stage, I wouldn’t change any of it for anything. And guys from the team, if you’re reading, know how special you are to me and I think the world of you.

What is iGEM?

There’s a semi-decent chance that if you’re enrolled at a Russell Group university in the UK and study something at least closely related to biology, such as biomedical sciences, chemistry, computer science etc. that you’ve heard mention of the phrase iGEM.

iGEM stands for the International Genetically Engineered Machine, and it’s a competition that runs annually out of Boston, Massachusetts encouraging undergraduate and postgraduate university students to get involved in biotechnology. This area of science has advanced such an incredible distance over a relatively short space of time that it’s vital we prepare the next generation of scientists to understand and further develop the tools we’ll need to use it. It usually takes place over a summer, in between academic years of study.

Team members from all over the world at the 2016 iGEM Giant Jamboree

Specifically iGEM is about synthetic biology, which fundamentally combines the principles of engineering (that being standardised systems with intercompatibility) with the techniques of molecular biology, bacteriology and an enormous array of other disciplines. This aim is realised through the use of custom-designed gene constructs that all have characterised functions, which can be combined together to create new constructs with new functions to solve a particular problem faced by society or develop a new tool.

"...just as the LEGO bricks in Beijing will match the LEGO found in Tennessee, all iGEM BioBricks are compatible no matter where on earth you stand"

Think of something like LEGO, for example. Each type of brick interlocks with virtually any other, the analogue in iGEM being ‘BioBricks’, which are genetic sequences with standardised prefixes and suffixes that allow them to be easily ligated together. Every year teams design more parts, building on the work of previous teams which is stored in the iGEM registry and available to everyone, not just competitors but research scientists all over the world. This is a crucial thing to realise, because just as the LEGO bricks in Beijing will match the LEGO found in Tennessee, all iGEM BioBricks are compatible no matter where on earth you stand.

Teams can vary in size and composition, but an example team might consist of say 10 students at undergraduate level. In my case, we had eight - myself and two further biologists, two biomedical science students and three from computer science. Five of us were in our second year of study, two from first year and one from third year at the time.

Our team assembled outside FabLab, Sunderland where we learned about 3D design

You then have to choose a problem to solve - Jake, one of our computer scientists came up with the idea of taking one of those fundamental aspects of iGEM (standardised systems) and trying to coming up with an electrobiological interface, and then producing free part designs that could be used to make them. The example given was build-your-own electronics kits such as those available from Hot Wires, usually given to children, wherein you make customisable circuits to perform a given task.

Long story short, it didn’t work very well but I’ll take you through the process. We learned how to design our own gene constructs using the SBOL Visual standard, had them synthesised and transform them into bacteria, test our constructs and record experimental data. There’s way too much to cover in this short article but I’ll give you a flavour of the sorts of things we got up to over our summer.

"Long story short, it didn’t work very well"

Lab training: You’ll no doubt receive full lab safety and technology briefings, and instructions on how to perform basic procedures alongside whatever specific experiments you wish to carry out. This is immensely valuable because it gives you a hands-on chance to get involved, and learn by success and failure. For example, I learned how to transform and culture cells, then measure growth and GFP fluorescence using industry standard equipment. I’m sure I don’t need to tell you how valuable that would be to a prospective employer or supervisor.

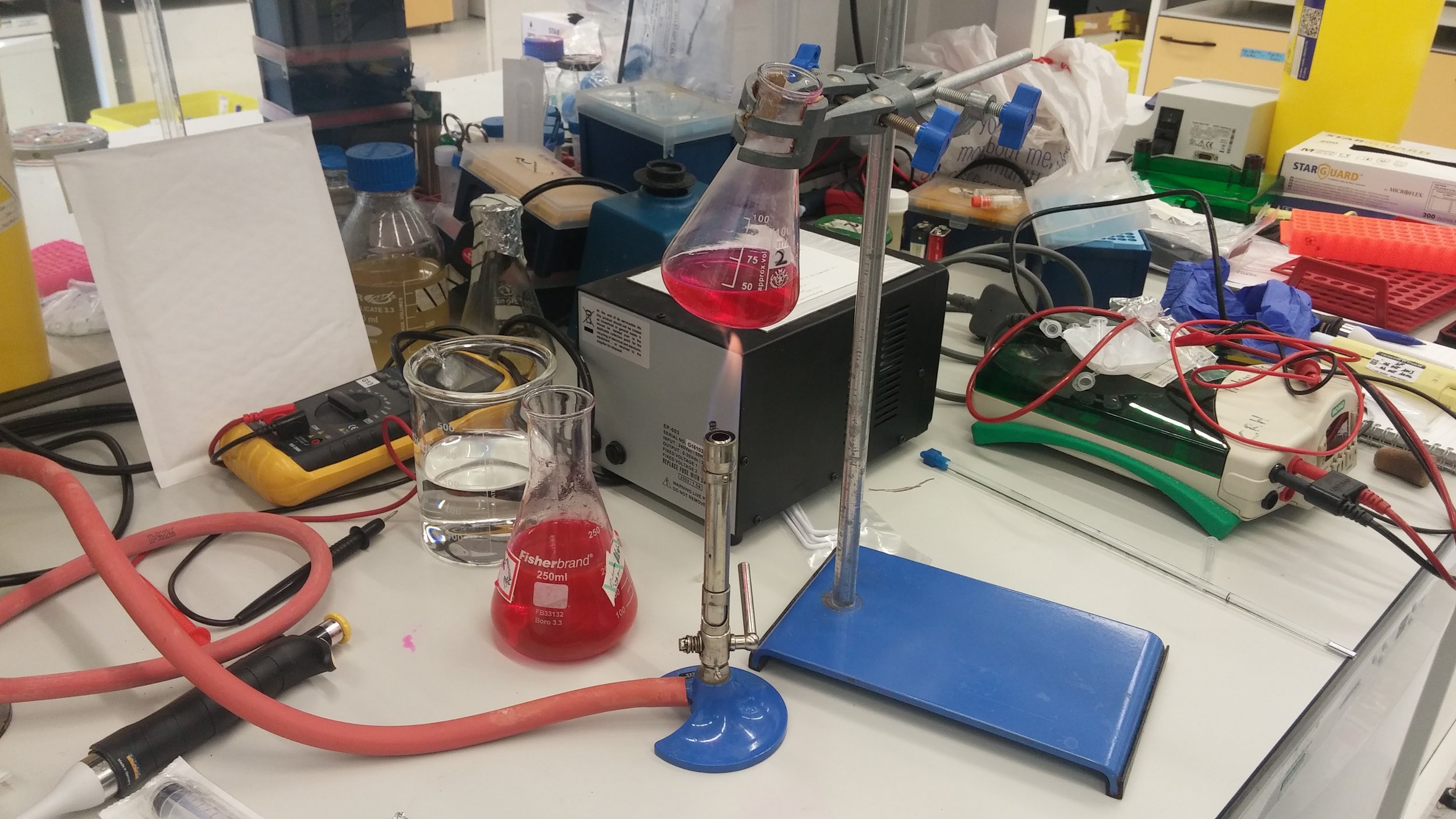

You'll have to come up with novel ways to solve problems

3D Design: One really enjoyable aspect of our project was that because it inherently required physical devices for our electrobiological interface, we had to learn how to manufacture things. To achieve this, we developed partnerships with a local FabLab at the University of Sunderland, a design and fabrication workshop, eventually moving to OpenLab close by at Newcastle University. I learned how to design 3D print models and engineer them for our purposes, soldering everything together and building testing circuits.

Academic Conferences: Of course what you’re doing is fundamentally academic (at least in part) and you need to be able to talk to others about it! Your iGEM work is judged based on a few different aspects, including the novelty of your work and characterisation of your designs, but all of these have to be communicated during your final presentation. To practice for these, you can go to iGEM meetups with other teams over the summer - in our case we attended gatherings in Edinburgh, Paris and Westminster before delivering our final talk in Boston. We designed academic posters and handout materials, and feeling the culmination of everything on that stage was pretty overwhelming.

"You’re not just let loose on the world with big ideas and clumsy hands - you’ll work very closely with academic support"

Support: You’re not just let loose on the world with big ideas and clumsy hands - you’ll work very closely with academic support, in our case a mixture of lab technicians, lecturers and researchers. They’ll be with you every step of the way, training you in the labs, helping you practice your presentations and keeping your organised and on track during the summer. The closeness to these academics that you’ll build up is enormously valuable, because the exposure can’t even be approached during a normal teaching course. I know first-hand that our mentors put in astronomical amounts of effort to get us through the process, and we wanted to work hard to make them proud.

Our team post-speech on the stage in Boston, MA

This doesn’t even approach the enormity of everything we experienced during the summer but if you want to see more, head over to http://2016.igem.org/Team:Newcastle to see our wiki which covers everything in much more depth. If you’re interested in getting involved, be sure to ask your school and don’t hesitate to drop me a line at the contact form if you want to learn more.

How NOT to Choose A University

Just as there are many excellent ways to help you choose where you might want to study, there are a few that are abjectly, objectively terrible that I highly recommend you avoid.

1. League Tables

Let’s get this one out of the way first, league tables are a waste of mine, yours and everyone else’s time. They are inconsistent with each other, all use different metrics and the positions jump around so much year to year that you’d think these departments were in constant flux. This is obviously true to a very small extent given that staff and module content might change in their minutiae, but newspapers are writing them to sell newspapers and websites are writing them for clicks and ad revenue.

If you are going to insist on doing this, then just avoid choosing somewhere that’s right at the bottom of the list across multiple lists, but other than that I really don’t think it matters. Employers don’t care, I don’t care, and you shouldn’t care either. If you’ve found somewhere you want to go, then go there and don’t let anyone give you sh*t for it.

2. It’s close to home

This is admittedly a very tough one, and will be contentious - but ultimately it comes down to being somewhere where you can live away from home. I think that one of the great aspects of university living is that it gives you control and makes you responsible for your own life.

I went to Newcastle University, approximately 2-3 hours by car away from where I live, which was close enough for me that I could still get back urgently if necessary, but crucially still allowed me to shape my own existence. Being somewhere else, even if it’s just student accommodation, even for just the first year of the course is an experience that I think everyone should have.

In that time you’ll learn by necessity to cook, clean, socialise and fundamentally become a more rounded member of society (or at least in theory). This won’t be for everyone, and that’s perfectly fine, but living in the sheltered bubble of home will I think deprive you of certain things.

"Being somewhere else, even if it’s just student accommodation, even for just the first year of the course is an experience that I think everyone should have"

3. The Minimum Grade Offer

I will examine this topic in more depth in the future, but remember that the minimum UCAS or grade requirements for a course DO NOT indicate how good that course will be for you.

These requirements indicate two things at best: Firstly, they reflect how competitive entry is, because if they have a fixed number of places but a ton of applicants, they need to be more selective by definition and raising boundaries is a good way of eliminating a large number of people very quickly. Of course it does stand to reason that better courses will have more applicants, but that does not necessarily have to based on quality of teaching - there are more than likely a multitude of factors at play that warrant further investigation.

Secondly, universities are playing a game with the UCAS system that plays on the above point. Schools want to fill all their degree places because that means more money, so it is reasonable from their perspective to inflate the entry requirements. More students will then assume that it’s a better course, apply for it, subsequently fail to make the grades, but the university will take them anyway. It’s a devious game but it’s easy to see how unwilling students can be preyed upon like this.

4. Your Parents Said So

The absolute worst reason of all, and something I’ve noticed multiple times when giving tours of Newcastle. Your parents, while they love you very deeply and I have no doubt want the absolute best for you, do not share your mind. They do not know as well as you do where it is you want to go and study, and if you are not able to stand up to them and tell them that, realise that it’s probably a good indicator of worse problems to come later on in life.

This is usually a particular type of parent, and it can lead to uncomfortable standoffs, but it’s far better to get it out the way - I myself have taken parents aside while doing tours and tried to recommend that they back off and allow the student to ask me questions. In cases where it’s plainly obvious that the applicant doesn’t want to be here, I’ll tell them that too, and there is absolutely nothing wrong with that. Go where makes YOU happy, not your parents. If at all possible, go to open days without them, and then have a second visit with them in tow if you’re still interested.

How to Choose A University

Here in the United Kingdom there are currently more than a hundred universities, each of which represents a viable place to study for new applicants. In this article I'll go through a few ways you can narrow down your search in time for the UCAS deadlines.

Keble College, University of Oxford

1. What subject?

The first and potentially easiest way of choosing your university is deciding what you might like to study. Here’s an easy exercise - if you’re applying with A levels or some equivalent through UCAS, open up a spreadsheet in Excel, write down the names of some universities (choose them at random if needs be!) and see if each place on the list even offers the course you want. Mark down the grades you need at each school and then rinse and repeat for as many subjects as you want - this is a nicely organised way of working through it and will make it easier to compare your options.

You’ll normally find all the relevant information on the university website, such as the aforementioned grade requirements, details of the application process (entrance exams, interviews etc.) along with aspects of the course that might be specific to that school - this is a great means of learning more about what each institution offers and might entice you towards or even repel you away from a particular place. This sounds negative at first, but in both cases it makes the final considerations simpler.

2. The Russell Group

Listen, I am not (or at least would not like to think I was) an elitist when it comes to education - I was happily state-schooled, and I have met people from an enormous range of backgrounds in the academic sphere who were all fantastically competent. By and large, I do not think that whether a university is part of the Russell group should sway your decision.

However, in my opinion, if you are considering biology or chemistry I would perhaps let it play on your mind just a tad. My reasoning is this: In such a university, your lecturers are more likely to have their own academic research going on which will enhance your chances of extracurricular opportunities in this area (see point 4). I think there are sufficiently few people taking maths and physics courses at present that demand exceeds supply for competent graduates in these areas, but this does not appear to be true as a whole across the sciences.

This is very much a generalisation, and many people will disagree, but this goes for all subjects of study - if you think that academia as the endpoint could be what you desire, (or industry research for STEM fields), then I think I would be doing you a disservice by not at least suggesting that you look into this aspect.

The IGEM competition as of present is only entered by research-focused UK universities