Portfolio Building For Medical Students

Portfolio building is one of those areas that I think most medical students are fairly dimly aware of - that is to say that most people have the understanding that portfolio is vaguely important and probably will become more important at some point in the future, but can probably be dealt with after medical school. And as someone with I think an extensive portfolio for my stage of training, I actually very much agree with this. For 95% of people, the goal of medical school should (I think) simply be to pass medical school and be a good and safe doctor for your patients. That should absolutely be where the priority is.

In this video however I’m going to address two things - why does portfolio building matter and for who specifically does it matter - and how to actually go about doing it. It’s often really difficult to know where to start, but we’ll get to that in a second and hopefully relieve some of those anxieties. It’s also quite likely that I’ll do a deeper dive video into each subtopic and flesh things out further, so if that’s something you’d like to see be sure to let me know in the comments.

So - why and when is portfolio building important? Your portfolio serves as a reflection of your skills, aptitudes, interests and competencies - as much as a portfolio can. Just like an artist, photographer or designer, when it comes to finding jobs, those employers will want to see evidence of a broad range of skills and experiences.

Now when we apply for our first jobs as doctors, the portfolio is not taken into consideration at all. Everything comes from your exam performance throughout med school and your performance on the Situational Judgment Test (SJT) at the end. There is no look at you as a person, no interview, no viva, no nothing - you are a number, not a person. And in fairness, there’s no good way to do this. You cannot feasibly interview 6,000 people or look through their portfolios. So for most people, the first time their portfolio will become relevant is likely Internal Medical Training or Core Surgical Training two years after they graduate, at the end of FY2.

This is why for most people I’d advise against investing huge amounts of time into the portfolio as a student - it does help you get a head start and reduce pressure later. However, in my view there are three major reasons why you may want to consider building your portfolio more aggressively as a medical student.

The first is if you aim to apply for an academic foundation programme post, now the Specialized Foundation Posts as a junior doctor, or indeed an academic clinical fellow job later down the line. These are posts that you take as part of your normal clinical training, and give you some protected time to work on projects you’re interested in, such as education or research.

The second is if you’re applying for a run-through specialty post straight after your foundation training. There are a small number of specialties such as paediatrics, neurosurgery and cardiothoracic surgery which recruit very early and are also very competitive - which also means your portfolio must be very competitive. There is not really going to be enough time to start working on these applications during FY1 because that’s not enough time to get things published, presented and so on.

Lastly, just because you want to! Lots of people are passionate about portfolio development and projects for no other reason than because they enjoy it - that’s great and should be rewarded too. And of course not everything has to be about portfolio.

Now let’s go through some of the common themes and things you can do to help build portfolio, using a combination of the different scoring matrixes for specialty training - mostly core medical and core surgical training. Each specialty is different - go and check out the relevant person specification for your specialty as they do vary in exactly what they want.

Extra Degrees

Exactly what it sounds like on the tin. Many programmes reward extra degrees, be they taken before medical school, intercalated into your medical school years or taken as a junior doctor. Now in my opinion extra degrees should never be done purely for the points, but especially intercalated degrees are a great way to learn more about a particular subject and develop a special interest, as well as giving you time to work on a project in that area. Typically the higher the class and level of a degree, the more points it is worth.

Academic Achievement

Medics are generally smart-arses but many specialties will reward being extra special brainy, or at least being very good at exams. This is usually demonstrated by graduating with honours, meaning you might have the degree title MBBS (Hons) or equivalent, and usually marks out the top 10% of the cohort by their academic performance. While obviously this is extremely difficult and is usually only worth a single point, it’s a nice thing to have if you can get it.

Audit & QI

These generally fall under the umbrella term of quality improvement projects. An audit is the most common project to pursue, and involves comparing the performance of your department to a known standard, say a clinical guideline. You might look at how long catheters are remaining in place on a urology ward, or how many patients are being given the correct dose of tinzaparin during their hospital stay. If you find a failing, you make some sort of intervention, re-assess the results a few months later and look for an improvement (or non-improvement) - this is an important part of being in a clinical team so showing evidence that you know how to close the loop on the audit process is a great thing.

Research & Publications

One of the more well-known facets of portfolio building is research, that is carrying out a project, generating some data, writing up that data and turning it into a paper, ideally which you can then get published in an academic journal. This definitely needs its own video, but you can consider surveys, focus groups, lab projects, teaching interventions, getting involved with larger projects such as clinical trials - there are many avenues into research and it’s one of the most ubiquitous ways of scoring points at specialty selection. Note that more papers isn’t necessarily better, and sometimes being able to demonstrate a range of academic skills across a variety of subjects might be better than 50 systematic reviews in your specialty.

Presentations

Once you’ve carried out your project be sure to present it, going to an academic conference and telling the community about your amazing work! This can be broadly divided into either poster or oral presentations, that’s presenting a poster about your work or speaking to an audience about it, and then national or international, with an international level conference usually considered the most prestigious. But especially at the student stage, any presentation is a huge achievement.

Prizes

Next prizes - these are one off awards that signify achievement in some domain. The most obvious ones are those for academic performance - say the highest performance on the written exams in your year, but there are loads of other ways to get prizes! There are countless essay prizes run for medical students in each specialty and usually not that many people actually enter. Scholarships awarded for research would also count, elective prizes, academic bursaries - there are so many ways to win prizes and I’ll leave some links down below.

Teaching Experience

The next one is teaching experience, which is a great thing to reward since all doctors are supposed to teach their juniors. This is split into two concepts usually, that being commitment to regular teaching over say a period of 6 months, and training in teaching, usually at least a minimum of a specified number of days. Don’t worry about these too much as they’re very easily addressable as a junior doctor, especially if you’re planning on working a year as a teaching fellow.

Leadership

Leadership can be demonstrated in a variety of ways - it might be being president or a committee member of a student society while at medical school, a course representative, representative of a national society, something like the BMA student team - basically anywhere where you have to make leadership decisions and can demonstrate a positive impact based on your work. Again, no rush to do this as a student, can easily be done as a junior doctor.

Commitment to Specialty

Lastly but not leastly, the other thing you can definitely build while a student is commitment to specialty, which most specialties are going to love. All of the above areas can be tailored to this, whether that is research in your subject of interest, attending conferences regularly, winning prizes related to the specialty, undertaking your electives in that specialty or belonging to the student society at university.

Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeds for Medical/PA Finals

Note: The following is an educational resource only, intended for use by medical and physician associate (PA) students for exam preparation. It is not a clinical guideline or substitute for medical training.

This was the first acute emergency I had to deal with as a junior doctor - I was all alone on an unfamiliar ward, my second ever day as a doctor, this in the morning and sepsis in the afternoon. It’s very frightening too - many medical emergencies can be somewhat occult, but upper GI bleeds are fairly bombastic and when someone is vomiting fresh, red blood in front of you it freaks you out. But we still have to deal with it.

GI bleeds do not necessarily fit our typical structure of these videos very well, because there are only really two key signs that you’ll see. More commonly I have seen melaena, that is the dark black, tarry looking stools associated with digested haemoglobin if blood has passed through into the lower digestive tract, or haematemesis, that is the vomiting of blood. This may be in small or large amounts too - the person may be retching small amounts into a sick bowl, or hosing large amounts all over the bed.

This raises an obvious question - why might this happen? What might predispose someone to a sudden upper GI bleed? While there are many causes, I think there are a few that it’s good to be aware of specifically for finals. The first is peptic ulcers - classically linked to either overuse of NSAIDS such as ibuprofen or naproxen, or infection with Helicobacter pylori. These ulcers are basically a sore that develops in the mucosa of the stomach, or the first parts of the duodenum, and they can erode through blood vessels causing significant bleeding - especially with duodenal ulcers, they can lie essentially on top of the gastroduodenal artery which is a classic exam question.

The second major cause of upper GI bleeding to know is oesophageal varices. These are enlarged submucosal veins that sit in the inferior third of the oesophagus, which most often appear due to portal hypertension, in settings such as chronic liver disease like cirrhosis or chronic right sided heart failure. When the pressure becomes too much, these veins simply burst open and start haemorrhaging enormous amounts of blood.

So what do we do in cases of upper GI bleeding? The main focus is really simple, which is firstly to stop the bleeding, and secondly to replace losses and maintain volume in the circulation. Let’s take a look at an exam scenario and work our way through it.

WORKED SCENARIO

You are a Foundation Year 1 doctor who has just arrived at work on the hepatobiliary surgery ward. The Charge Nurse appears and asks you to hurry to see one of the patients, Mr Sorinola. Mr Sorinola was admitted for management of his ascites secondary to severe cirrhosis and is awaiting an ascitic drain procedure. The nurse tells you that he has just vomited 1.5 litres of fresh blood into a vomit bowl and is continuing to retch.

We seek Mr Sorinola very quickly and examine him using an A-E approach.

A: Airway patent, patient maintaining own

B: RR 24, O2 sats 98% OA, symmetrical chest expansion, good inspiratory effort

C: BP 88/58, HR 120. Pulse weak and regular, HS I+II+0

D: Temp 37.4, PERL, BM 7.8

E: Vomit bowl full of bright red blood.

So what we have here is a man who is vomiting large amounts of blood and is haemodynamically unstable, as we can tell from his systolic blood pressure of less than 90 and his tachycardia.

What are we going to do? It makes sense to call for help as soon as possible here. Specifically we’re going to activate the massive haemorrhage protocol - your local trust may have specific guidelines on this so follow those - the JPAC, one of the advisory committees for blood transfusion, suggests that a pragmatic definition of when to activate this may include the loss of 70ml/lg within 24 hours, 50% of total volume in less than 3 hours, or indeed a systolic BP of less than 90 or a heart rate of 110 or more. We’ll cover the MHP in more detail in another video, but for the sake of this context, it’s going to get us the blood products we need to appropriately transfuse our patient, typically 4 units of red cells and 2 units of fresh frozen plasma coming first.

On top of that of course, let’s call our registrar or anaesthetics for some more experienced hands.

And we need to transfuse because resuscitation is the name of the game here. The main goal is supporting circulation, so getting two wide bore venous cannulae in is very important - to illustrate the difference this can make, pushing a litre of fluid through a blue cannula, that is a 22G cannula takes 22 minutes. If instead we put a grey cannula in that reduces to 6 minutes, and you can push 1L through an orange, a 14G cannula in just 3½ minutes.

An urgent set of blood markers need to be taken so we know what we need to give - including a full blood count, group and save, coagulation screen and so on. Cross matched and group appropriate blood is the best thing we can give, but obviously O-negative blood is available in emergencies.

So now let’s think about management - what are we going to do about the bleeding site? The answer is usually going to lie with an endoscopy. This is going to mean calling the on-call endoscopist, which may be a gastroenterologist or a surgeon, and they may ask for the Glasgow-Blatchford score.

This is a risk stratification tool for people with an upper GI bleed and helps to decide whether or not they are likely to need intervention. It’s worth noting that use of this score is somewhat controversial for inpatients, but I have been asked for it before.

We’re doing the endoscopy ultimately to decide whether or not the bleeding is variceal, that is coming from ruptured varices. Once they have had endoscopy, you may then decide to calculate the Rockall score, which estimates the risk of a rebleed as well as the mortality risk for that patient.

If we assumed the bleeding was non-variceal, and was perhaps coming from a pseudoaneurysm or ulcer, the bulk of treatments are done during the endoscopy. The endoscopist may decide to thermally coagulate the site using heat, use surgical clips or inject medicines like adrenaline to cause vasoconstriction and stop the bloodflow. Once the bleeding has been quelled, the patient should be given a proton pump inihibitor such as omeprazole to protect the lining of the stomach and promote recovery.

But in our patient the endoscopist finds that the cause of the bleeding is ruptured oesophageal varices, which have likely developed secondary to our patient’s cirrhosis.

Before we even get to this stage however, if you suspect your patient has bleeding oesophageal varices, NICE recommends giving terlipressin immediately to constrict the smooth muscle in the vessels and reduce bloodflow, alongside prophylactic antibiotics as per your trust guidelines. Oesophageal varices are usually managed via band ligation, in which a rubber band is placed around the bleeding vessel which cuts off the bloodflow and stops the bleeding. If this does not work, then TIPS (a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt). As you might be able to decipher from the name, this procedure involves diverting (shunting) bloodflow from the portal vein to the hepatic vein, which allows blood to bypass the liver and therefore reduces pressure in the portal system and thus the bloodflow to the varices.

The only other (somewhat rogue) option is a balloon tamponade, sometimes known as a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube. This is essentially a tube inserted through the mouth or nose that contains a balloon, which is passed through to the stomach - one balloon inflates inside the stomach, and another inside the oesophagus, putting pressure on the gastrooesophageal junction and stopping bloodflow to the varices. I’ve never seen it used in practice, but they are there in case of emergency.

After all of this review NSAIDS, anticoagulants, antiplatelets, come up with a safety netting plan and refer to appropriate specialists for aftercare and further planning.

How Long Does It Take To Become A Doctor?

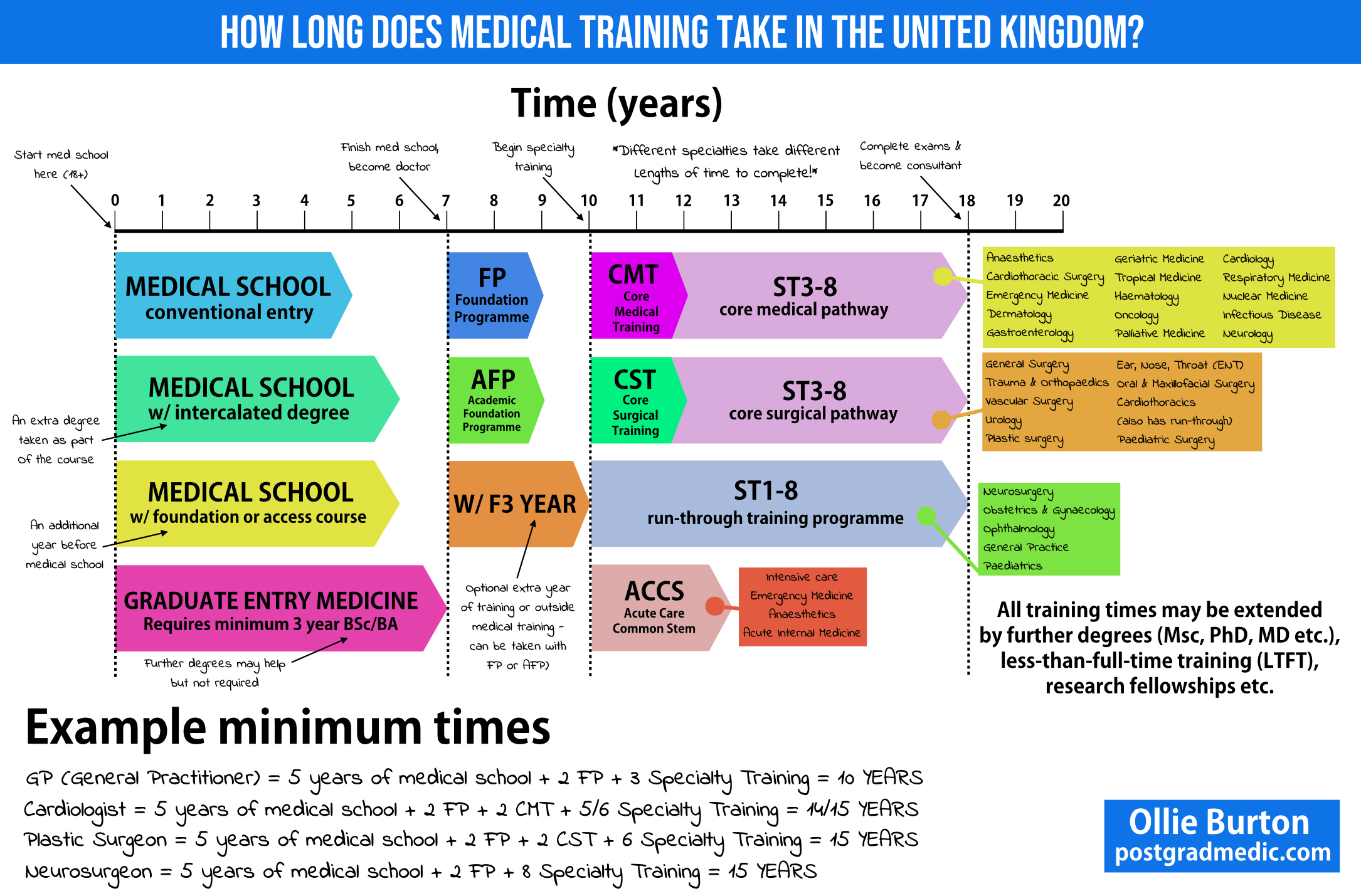

I get asked all the time, especially by friends and family - just how long are you going to be at medical school? It’s something all us medical students need to think about before we start, but even having done a lot of research before I applied, there was still left to learn that I’ve picked up since getting here. I’ve put together an infographic that illustrates the broader guidelines.

Right then, standard entry to medicine. You go when you’re 18 after completing your A levels, entering into first year, and these courses are usually 5 years long. That means you’ll enter at 18 and finish at 23. Some UK schools have an optional or compulsory intercalated degree year for a Bachelor’s or Masters, which would add another year for a total of 6. This would be the same if you completed a Foundation or Access to Medicine course too. Then there’s graduate entry medicine, which requires at the very least an undergraduate degree to complete, which is a 3 year investment. However the tradeoff here is that you essentially get to skip a year of the course due to the content being compressed, which makes it 7 years long.

Congratulations, you’ve finished medical school and passed your final exams. You are now able to call yourself Doctor with some letters after your name such as MBBS or MBChB - they’re all equivalent, don’t worry. This is the point at which you start earning money. You then have to complete 2 years of Foundation Training as a junior doctor - in the first year you have a provisional license to practise medicine, with the full license for unsupervised practice being obtained after that first year and then you complete the second year of training with that license. During each of these years you’ll rotate between various specialties and gain a basic set of core competencies.

You can also apply for the Academic Foundation Programme instead, which takes the same amount of time but gives you some protected research time you can spend working on an academic research project or in an educational setting, for example. Some people also choose to take an extra year out here as F3, either to have a break from training or pursue other projects, teach or maybe to get themselves ready for specialty training.

At this point you then need to decide what specialty you want to do and things get a bit more complex! Let’s start simple and say you want to become a General Practitioner - this is currently the shortest training pathway and takes 3 years after completing foundation training, meaning your total medical school journey, assuming you started at 18 in the conventional pathway is 10 years long.

Let’s say you want to be a cardiologist - you’ll need to spend another two years in Core Medical Training, CT1 and CT2, which almost all medical doctors will do. After that, you then apply to go into specialty training specific to cardiology and enter at the ST3 level, or Specialty Training 3, your 3rd year after foundation. You then stay on this programme and go through four more years to ST7, with the option of a final ST8 year to subspecialise and then become a full, bona fide consultant. While you’re in specialty training you are known as a specialty registrar, which is still technically a junior doctor.

Let’s now give a surgical example - you now want to be a orthopedic surgeon. Similar to medical programmes, you need 2 years of core surgical training, CST1 and CST2, which almost all surgeons will do. After that it’s 6 years of specialty training, agains starting at ST3 and ending at ST8 as a consultant surgeon. The other major pathway after foundation training is run-through specialty training programmes. This means that instead of having to do core training and learning the basics that overlap with other specialties, you focus on the end goal right from the start and only do training relevant to that job. A good example is neurosurgery, where instead of CST1 and 2, you begin right away at ST1 and go right through to ST8. There are advantages and disadvantages to this - there is only competitive step, entry to ST1, so once you’ve got your foot in the door you’re sorted until the end. Obviously if you change your mind it’s a lot more difficult to change direction because you have not done the core training which would allow you to enter a different specialty later.

The last pathway we’re going to discuss here is ACCS - the acute care common stem training programme. This pathway focuses as the name suggests on four acute care parent specialties - intensive care, emergency medicine, acute internal medicine and anaesthetics. This pathway takes 3 years to complete, and allows you to undertake higher training in those parent specialties. Anaesthetics for example also has its own core medical training programme, so be sure to look more at CMT and ACCS if that’s something you’re interested in.

So that’s a very quick overview of higher medical training through junior and senior ranks. We said earlier for a GP you’re looking at 10 years minimum investment. For most others it’s another 5 years on top of that - you could go in at 18 and be 33 as a consultant. Of course that assumes you don’t do anything else, like Masters Degrees, PhDs/MDs, research fellowships, teaching placements etc which would extend it further.

Top 5 Tips for Medical Interview Success

1. Knowledge Base

Medicine is a career that encompasses a very large number of skills, including but not limited to ethical reasoning and strict adherence to protocol. Doctors and other healthcare practitioners are often in positions of power relative to their patients due to the nature of the occupation, and are therefore expected to act in certain ways and follow certain behaviours. Understanding their ethical and logical guidelines is therefore a fantastic place to start - I recommend reading ‘Tomorrow’s Doctors’ and ‘Good Medical Practice’, as well as getting to grips with the four pillars of medical ethics. Understanding these core elements will help you approach most questions from first principles instead of having to rely on learned answers.

Alongside this, be able to talk about a couple of medical cases from research papers or the news that interest you - that will demonstrate your initiative and willingness to further your own knowledge.

2. Practice Answering Questions

Just like the UKCAT, BMAT, GAMSAT or any other exam, the best form of revision is to practice doing questions. There are a ton of free resources out there in this area, look at places like The Medic Portal, my own website (postgradmedic.com) or (dare I say it) The Student Room. Have your friends or family members ask you random questions so you’re forced to think on your feet - even if you don’t think they’re likely to come up. Sometimes being put on the defensive and into an uncomfortable scenario is the best way to get used to thinking and answering in a more structured way.

3. Practice Under Pressure

Of course the other element of medical interviews (as with most assessments) is the aspect of time pressure. This is particularly true in MMI format interviews where you may have no more than a few minutes to answer a particular question, particularly if it’s a probing question rather than the stem of a discussion. With this in mind, when practicing with family or friends make sure to have them time you for 2-3 minutes per individual question - this will make it very hard in some cases, but if you can achieve that then on the day it should be easy.

4. Reflective Thinking

Doctors (and medical students) are required to perform reflections throughout their careers to consolidate what they have learned and set action plans for self-improvement. Furthermore, most medical schools (particularly at graduate-entry level) demand some level of work experience or exposure to a healthcare setting. The reason for this is to give you a chance to evaluate if medicine is truly the right career for you. Based on your experiences at school or university, at work, while volunteering - why do you think you would make a good doctor? What have you observed? What do healthcare professionals do every day? What did you like about what you saw, or conversely what was shocking or disappointing?

Gaining insight into your own thought processes will be enormously helpful for your interview and for your time at medical school and beyond.

5. Relax

Probably the last thing any of you wanted to hear, but it’s vitally important. Remember, you’ve made it to interview now, so there’s a very good chance that you are completely suitable for medicine. The role of the interviewer is not to grill you so you can be eliminated, but instead to allow you to demonstrate your competence and allow them to get a feel for ‘the real you’. Let your personality come out and answer everything honestly. A medical interview is fundamentally a discussion and that’s how you should approach it.

Make sure to get a good night's sleep the night before (stay overnight close by if necessary) and have something to eat. I'm sure you'll do great - good luck!

The Pros and Cons of Graduate Entry Medicine

While undergraduate courses are seen as the 'standard' entry route into medicine, graduate-focused programmes are responsible for producing a huge number of doctors, and may offer a better deal for applicants who already hold degrees.

Pro: Saving a Year

Let’s start with an obvious one. Graduate entry programmes allow you to complete a medical degree in four years rather than five, which is obviously a good thing if you’re eager to get into practicing as a doctor. If you didn’t make the grades first time around for example, you could complete an undergraduate degree by 21, and then graduate as a doctor at 25, only two years behind those that started at 18, with all the extra experience and opportunities to boot.

Con: Losing a Year

Of course, this also has its downsides. Medicine has a reputation for being an incredibly challenging degree, and graduate schemes cram the already huge amounts of material into a shortened time frame. If you’ve been out of education for a while or are worried about finding the academic transition difficult, it might be worth considering five year courses to make your life just that little bit easier.

Pro: More maturity

On a similar note, because of the increased average age, your cohort should (at least in theory) be a bit more mature than a comparable cohort at 18 years old. Of course that’s not to suggest that undergrad-entry medical students are immature at all, but simply by virtue of being older people are more likely to be more collected and capable of managing their lives and social relationships properly.

Con: Money

This is probably more noticeable to those that have been employed in a real-world job, in that you absolutely will not be able to work while studying and your income will suffer as a result. In a similar vein to before, your friends will start to become established in their careers sooner than you, and basically you will be on low-income posts for a while even after graduation.

Pro: Funding is available!

Given the recent removal of the nursing bursary, I’m not sure how much longer this point will remain true, but for now at least a graduate-entry medical programme can be funded through Student Finance England. There’s a not-tiny sum that must be paid upfront (approximately £3375), after which a standard student loan is available to cover the rest.

Con: Qualifying Older

It seems like a stupidly obvious thing to say, but it’s worth thinking about. As of right now I’m 21 years old, so this won’t be as large a problem, but let’s take a reasonable guess and say that the average age on my course is around 25. It takes 4 years to complete the degree, which will make most people around 29/30 when starting work as an F1, a notoriously stressful and time-intensive role. By that point most people’s friends will be settled down and may have children, and if you have significant responsibilities or relationships of your own, a medical degree could be very disruptive. These things can definitely be managed properly, but it will make some elements of more life more difficult.

Pro: Wider Range of Backgrounds

Because graduate-entry courses demand a first degree as part of the application process, by necessity every single person on the course will have at least an undergraduate degree under their respective belts. While some schools will only accept science graduates, there a few (including Warwick where I go) that happily take arts and humanities students too. This leads to a fantastic array of knowledge and unique perspectives that serve the year very well as a whole, particularly when it comes to group work.

Con: Competition

Getting a place on a graduate entry scheme is rough. Competition is comparatively more fierce because everyone has more experience and knowledge than the typical school leaver. This leads to either the use of the GAMSAT (a 6 hour slog of an exam that tests your reasoning across humanities and natural sciences) or higher cutoffs in the UKCAT and BMAT. In 2013, for example, Warwick (one of the two grad-only medical schools) had close to 3000 applications for about 170 places. I did the maths, and for 2017 entry (considering only home applicants for undergraduate and postgraduate courses) at undergraduate level there were 9.2 applicants per place, with 25.8 applicants per place for graduate-entry courses.

You’ll get to be a doctor

But of course, the ultimate positive from a graduate-entry scheme is that at the end of it, you’ll get to be a doctor. That’s the ultimate reason why any of us that applied to study medicine did so, and regardless of whether you choose a four year or five year scheme, we’ll all be in it together doing what we set out to do.

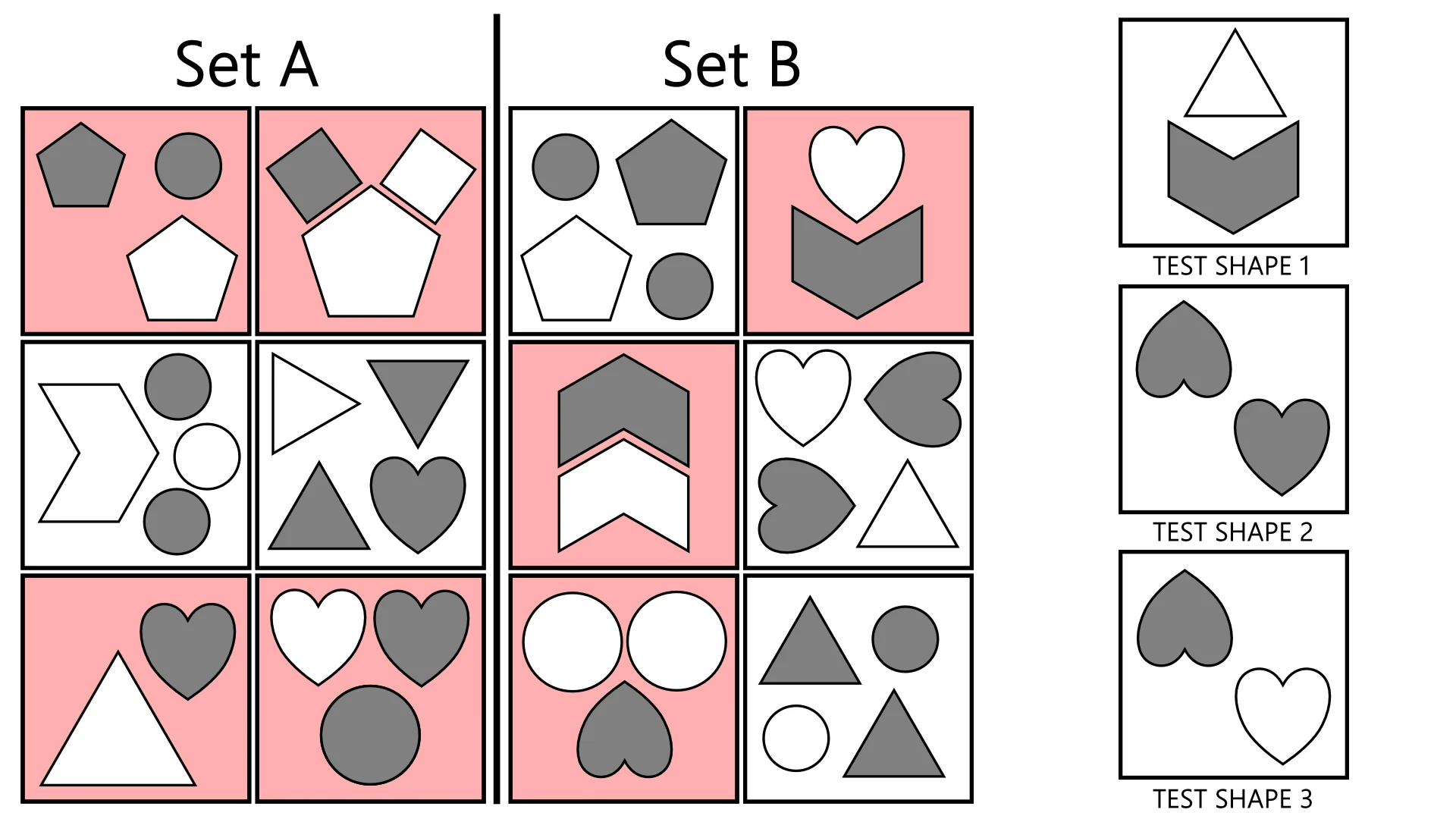

UKCAT Abstract Reasoning - SCANS Method

The Abstract Reasoning subtest of the UKCAT can appear punishingly difficult for test-takers, even after a good amount of practice. On average you have on the order of 45-50 seconds per question, so you need to become adept at spotting the rules governing each set quickly and confidently. Therefore it’s a good idea to go in knowing what sorts of things to look for, which is what this article is all about.

A great way to start is the SCANS method. This, as you might have guessed, is an acronym and mnemonic device that helps you structure your approach to each questions.

A sample Abstract Reasoning pattern - use SCANS to try and work out the rules!

S - Shape: What shapes are present?

C - Colour: Is the colour of any shapes present relevant or consistent between boxes, particularly in combination with the previous step?

A - Arrangement: Where in the box are the different shapes arranged? Take note of colour here, as arrangement questions are often conditional on another factor i.e. if the circle is black, the squares are at the bottom.

(If faced with a pattern using lines or clock faces etc, use A to represent ANGLE instead, noting how many acute/obtuse angles there are per box and if the angle faces another element).

N - Number: How many shapes of each type are there, how many sides do they have and what is the total number of sides and right angles in each box?

S - Size: How does the size of each shape vary between the boxes, and does it correlate to colour, arrangement or a conditional feature, such as the presence of another shape or the total number of sides in the box?

Hopefully this helps - there’s a tendency for new candidates to get flustered and give up on trying to practice the abstract reasoning subtest, but it’s just a case of training your brain through practice. You’ll start to pick up speed over a week or two and then you’ll perform much better than guessing through blind chance.

Sample UKCAT Abstract Reasoning Questions

Here you'll find some sample UKCAT Abstract Reasoning questions that I've created for you. Use the controls at the sides or click the thumbnails below to change question. Hover over the image and highlight the text to reveal the solution.

Medical Interview Question Bank

Here's a list of practice medical interview questions I've devised for you, very typical of the types of things you might be asked at either a traditional interview or an MMI. Writing structure guides for these questions is going to be a long-term project for me, but I'll link each one to my thoughts on it as each article is completed.

They are sorted very roughly by theme, but at this point are intended as prompts, interesting ideas that you might want to think about. If you end up writing your answers down (which I suggest), I'd love to hear from you so I can add new ideas to the existing articles so more people can make use of them. Enjoy!

MOTIVATION & BACKGROUND

What will you do if you are unsuccessful in gaining a place at medical school during this application cycle?

Talk about a time in your life when you experienced an academic failure, and then what you did to overcome it.

How have your current studies (be it A levels or university education) prepared you for medical school?

Where would you like to practice medicine after you qualify?

Do you have any personal experience with the death of friends or family members? What was it like to deal with that loss?

Medical school requires a lot of revision and independent study outside the classroom. Do you feel that you would be able to cope with this?

Have you overcome any biases in your life?

Who are your heroes and why?

If you were not successful in gaining a place at medical school this year, would you apply again, and if so how many more times?

We have received 3,000 applicants for 150 places at this medical school. Why should we pick you?

What area of medicine or medical specialty interests you the most, and why?

What elements beyond simply providing healthcare to patients do you think the role of a doctor in society holds?

If you could watch any medical procedure being performed, what would it be and why?

Medicine has a reputation for being a stressful career. What will you do as a medical student to relax and reduce your stress when things get difficult?

What is your greatest strength, and why does it make you suitable for a career in medicine?

What traits or qualities would you look for in a doctor if they were treating you?

Why do you want to be a doctor?

What would you do if you couldn’t go to medical school and had to pick another career?

Why do you not want to be a nurse, paramedic or another form of healthcare practitioner?

Give an example (based on your work experience) where you had to solve a conflict, and explain how you did so.

WORK EXPERIENCE

Give an example (based on your work experience) where you displayed useful initiative.

Give an example of when you demonstrated leadership skills during your work experience.

What do the terms ‘empathy’ and ‘sympathy’ mean, and how do they differ?

Give an example (based on your work experience) when you had to work as part of a team and were not the leader.

Give an example of a time during your work experience where you handled a stressful situation.

MEDICAL AWARENESS

How has the public perception of doctors changed over the last 50 years?

“Lawyers say if you never get sued, you’re not a good doctor” - Dr Ranjana Srivastava

Do you think this is true?

Discuss what is meant by Autonomy, and give an example of it in a healthcare scenario.

Discuss what is meant by Beneficence, and give an example of it in a healthcare scenario.

Discuss what is meant by Non-maleficence, and give an example of it in a healthcare scenario.

Discuss what is meant by Justice, and give an example of it in a healthcare scenario.

What are the consequences of an ageing population for the NHS?

Should doctors or politicians be in charge of running the NHS?

What do you think about the recent doctors’ strikes, particularly when emergency care was withdrawn?

Why might the practise of medicine be different in the UK and developing countries?

What do you think about the ethics of private healthcare?

You have recently qualified as a doctor, and your friend asks you to take a look at a rash they have developed over the last week. Do you agree to do this?

Is it correct that people can be detained under the Mental Capacity Act?

Is it more important for a doctor to be highly knowledgeable, or to be able to communicate well with their patients?

Should surgeons get to know their patients before operating on them?

Talk about a medical case in the news recently that interested you.

What do you think about the phenomenon of the ‘postcode lottery’, and is it fair?

Do you think we need more nurses or doctors?

If you became a doctor, do you think your friends or family would be okay with you treating them, and would this be acceptable?

Do you think that newly qualified junior doctors should have a minimum term of service in the NHS, and if so how long should it be?

What is the placebo effect, and should NHS doctors be allowed to use it on their patients?

As of 2016, only 52% of junior doctors that finished their two years of foundation training proceeded straight into GP or specialist training programmes with NHS England. Why do you think this is?

If you could change one thing about healthcare in the UK, what would it be?

Why do some medical students drop out before finishing their course?

Is there an area of medicine that you know for certain does not appeal to you, and if so why is that?

Do you have a favourite medical-themed TV series or book? What do you think about the representation of doctors in the media?

Why is ‘bedside manner’ important for doctors?

Should euthanasia be available through the NHS for all patients?

Do you think that the lives and social responsibilities of a GP and a heart surgeon are very different?

Should cosmetic surgery be available through the NHS, such as breast implants or nose alterations?

Do you think doctors are overpaid?

Why is doctor-patient confidentiality important?

If you were one day placed in charge of the NHS, how would you allocate the budget for the coming year?

Doctors display a higher prevalence of mental illnesses than the background rate in the general population, particularly among young members of the profession. Why do you think this might be?

Do you think that teamwork is important for the NHS to function properly?

With increasingly accurate anatomical models and computer simulations, do you think that cadavers are still necessary for medical education?

What is the difference between a junior doctor and a consultant?

How many attempts at in-vitro-fertilisation (IVF) treatment should women receive on the NHS, and should we continue to offer it for free?

Should homeopathic treatments and alternative therapies be provided by the NHS?

Give an issue that is important to the NHS today and discuss it.

What are the four pillars of medical ethics, and how do they relate to healthcare?

SCIENCE

What is blood for?

Why is Huntington’s disease maintained in the general population, when it kills those who suffer from it?

How does antibiotic resistance work and why is it a problem for the NHS?

Tell me about the MMR controversy and what the subsequent effects on public wellbeing were like.

What are the limitations of medical research?

Which are more dangerous, bacteria or viruses?

What is pain?

What consequences does the practice of medicine have in terms of human evolution?

Why are stem cells useful for medical treatments, and why might their use be controversial?

How do vaccines work, and should they be compulsory in the UK for children?

ROLEPLAY SCENARIOS

You are a surgeon in charge of assigning organs to transplant patients. A donor heart has become available, but there are two patients that need it. One is a 20 year old homeless man who is a regular drug user, and the other is a 40 year old woman with two children. Who gets the heart?

You are a second year medical student and have just finished your final exam of the term. On your way out of the venue, you hear several classmates talking and it becomes clear that they are writing down the questions and answers to give to the students taking the exam next year. What do you do?

You are working as a junior doctor on a hospital ward, and you hear shouting from the next room. Upon further investigation, you learn that a patient was shouting at one of your colleagues, who is a foreign doctor and trained in India. The patient is using racial slurs and demanding to see an English doctor. How do you approach this situation?

Imagine you’re a doctor and a parent brings their child into A&E. The current waiting time is more than an hour, and they are angry that the wait is so long. How do you deal with this situation to calm them down?

You are a medical student shadowing a consultant surgeon, and you are both scrubbing up to enter the operating theatre. You are ready to go inside, but catch a glimpse of the surgeon taking a swig from a bottle in his locker, which he hastily returns when he sees you looking. What do you do?

Place your hands by your sides or in your pockets. Without moving them, explain to someone how to tie their shoelaces.

You are a doctor treating a young child who has suffered damage to the insides of their ears and has lost most of their hearing. The ward consultant recommends they be fitted with a cochlear implant, but the child’s mother is also deaf and does not want the child to have the implant. What do you do?

While backing your car out of the driveway, you accidentally ran over your neighbour, Mr Collins’ new puppy which had gotten into the road. You have 5 minutes in which to break the news to Mr Collins.

Imagine that two parents have asked that their son be given a genetic scan for Huntington’s disease, as the father has recently begun to suffer from symptoms of it. The test returns positive, but the parents decide that they will never tell the child. Do you intervene and tell the child yourself?

Imagine that you and your best friend have both applied for the medical course at this university. We have one place left to allocate, for which the two of you are competing. You have been offered the place, which you may accept or reject. Your best friend will be devastated if they do not gain entry. What do you do?

Imagine that you’re a medical student on placement or junior doctor on a hospital ward. A patient’s blood sample has gone missing, and you need to explain to them that another one needs to be taken.

ABSTRACT

What should the penalty be for falsely impersonating a doctor in the UK?

If you could change one aspect of yourself, what would it be and why?

The development of new genetic engineering tools such as the CRISPR-Cas system could potentially allow for genetic abnormalities to be fixed before a baby is born. Is this ethically right, and should we continue research into this area?

With the rise of automation, could all doctors one day be replaced by robots?

Should previously convicted criminals be allowed to become doctors?

Do you think that entrance exams like the UKCAT and BMAT ensure that the best people become doctors, and should we continue to use them?

How would your life change if you suddenly became unable to read?

What risks do doctors pose to the public?

Is it wrong for doctors to be smokers?

Is it better (in terms of ethics) to provide healthcare to foreign nations that need aid, or simply send them money?

Medical doctors, dentists and veterinarians can all use the title ‘Dr’, as can those who hold PhDs. What do you think about this, and should the situation be changed?

Tell me about one of your friends that you think would make a good doctor, regardless of their interest (or lack thereof) in a medical career.

Do you think there should be an upper limit on the number of times one person can apply to medical school?

Do males or females make better doctors?

Can you tolerate the sight of blood or wounds? Why do you think they make some people uncomfortable?

It is widely accepted that ‘everyone makes mistakes’, but sometimes when doctors and surgeons make mistakes, people can get hurt. Should doctors be immune to prosecution in the UK when this happens?

Why is medicine sometimes referred to as an ‘art’?

Should doctors get involved in politics?

Who was Hippocrates and why was he important?

Why is entry to medical school so competitive?

If you could instantly cure one illness all across the world in all people suffering from it, what illness would you choose?

Should military doctors have to treat enemy combatants?

Should you give money to beggars?

Do doctors make good life partners?

How would you describe what medicine was to an alien that knew nothing about it?

Why are bandages usually white?

If you could choose a way in which to die, what would it be?

What are the most important elements of communication?

If you had to write the questions for medical school interviews, what would you ask the candidates and why?

What invention or discovery from history do you think changed medicine the most?

Why do so many people find the Abstract Reasoning section of the UKCAT difficult?

What excites you the most about gaining a place at medical school, and equally what frightens you the most?

Is it okay for doctors to diagnose and treat themselves?

Do you think that cannabis should be legalised in the UK?

Should the sale of cigarettes be banned in the UK?

Should the religious convictions of patients be taken into account when delivering their healthcare?

In the USA, the primary medical qualification is the MD, which can only be taken as a graduate student. In the UK, medicine is an undergraduate course that can be taken at 18. What are the advantages and disadvantages to medicine being a graduate-only course?

Do you think that people with major disabilities such as deafness or blindness have any unique advantages or disadvantages when practicing medicine?

How do the healthcare systems differ when comparing the USA and the UK?

Would you prefer to practice medicine in a rural area or in a city?

Why are doctors and dentists different?

If we were to contact one of your teachers/lecturers other than your UCAS referee, what do you think they would say about you?

Should doctors be re-tested after qualification to ensure they are still fit to practise?

How do surgeons differ from doctors?

How does your family feel about your decision to attend medical school and become a doctor?

Why are medical degrees longer than standard undergraduate degrees in the UK? To combat the shortage of doctors we should simply reduce this to four or even three years. Discuss.

When you have personal problems, who do you talk to about them?

Medical interviews and entrance tests are intended to select for positive traits associated with good doctors. What negative traits might the same tests also select for?

How has your upbringing and background prepared you for a career in medicine?

Should experimental treatments be available through the NHS to patients when all other potential options have been explored?

Should doctors or nurses be the first point of contact in primary care?

If you could ask a medical consultant who was about to retire after thirty years service in the NHS one question, what would it be?

Sponsored Link: MMI Interview Question Bank & Answers from Blackstone Tutors

What to Wear to your Interview

This is a question that causes a lot of people undue stress, and one that thankfully has a fairly simple set of answers. Of course, there is no ‘golden ticket’ dress code, just as there is no perfect answer for interview or infallible revision tip with which to ace the UKCAT. However, I still recommend planning ahead what you’re going to wear on interview day so you have at least one fewer thing to stress over.

You should always dress suitably to the situation you are expecting, so let’s analyse this aspect first. What do you want to communicate about yourself to the interviewer via your clothing, or rather what are they likely to think when seeing you for the first time? The medical school is recruiting for future doctors, so ideally you should look smart, reliable and be generally well-presented. It is better to wear more subdued clothing because that way the interviewer is not provided an instant reason to dislike you - leave the ostentatious items at home.

This is of course even more true if you’ll be attending an MMI-format interview, where you’ll be making a crucial first impression multiple times.

Please note - the following recommendations are not hard-and-fast rules for acing your interview. Instead, they are tried-and-tested fashion combinations that would be appropriate for business wear and considered ‘safe’.

Making a good impression is crucial.

For Men:

As with most formal occasions, I think men have it much easier, because you should be wearing a suit. Opt for a dark colour, such as black, grey or navy blue. Make sure that the jacket fits well around your shoulders when you’re buying it, because it is extremely difficult to alter the width of the shoulders, whereas the sleeve length is easier for a tailor to fix. Similarly, your trousers should fit you well in the waist, and the length can be fixed afterwards to suit (no pun intended).

A black or grey suit should usually be paired with black shoes, but you could opt for brown as well, particularly if worn with a blue suit. Your shirt should be a light tone that contrasts the jacket - plain white or a light blue is safe. I recommend wearing a tie, the colour of which should again contrast the colour of the jacket. For dark suits, I would recommend a red or blue tie with a simple pattern or no pattern at all, although any plain colour would be ideal.

Accessorise with a watch and tie clip, unless wearing a waistcoat. Your belt should match your shoes. The reason I say this about watches is that pulling out your phone to check the time if you need to looks incredibly unprofessional, even in this age. Make sure that any facial hair is well-groomed, with clean shaven being arguably the safest look, but I think virtually anything (including stubble) can work well as long as it’s tidy. If you wish to wear cologne or aftershave, choose something subtle and not heavily fruity - these are better saved for clubs.

If for some reason you are unable to find a well-fitting suit in time (as I was not, because I received the call to interview during the Christmas holidays) then I would recommend pairing a pair of black formal trousers with a dark V-neck jumper over a collared shirt and tie. All other rules apply as before, and definitely don’t wear a tie clip in this case.

Female-friendly update coming very soon!

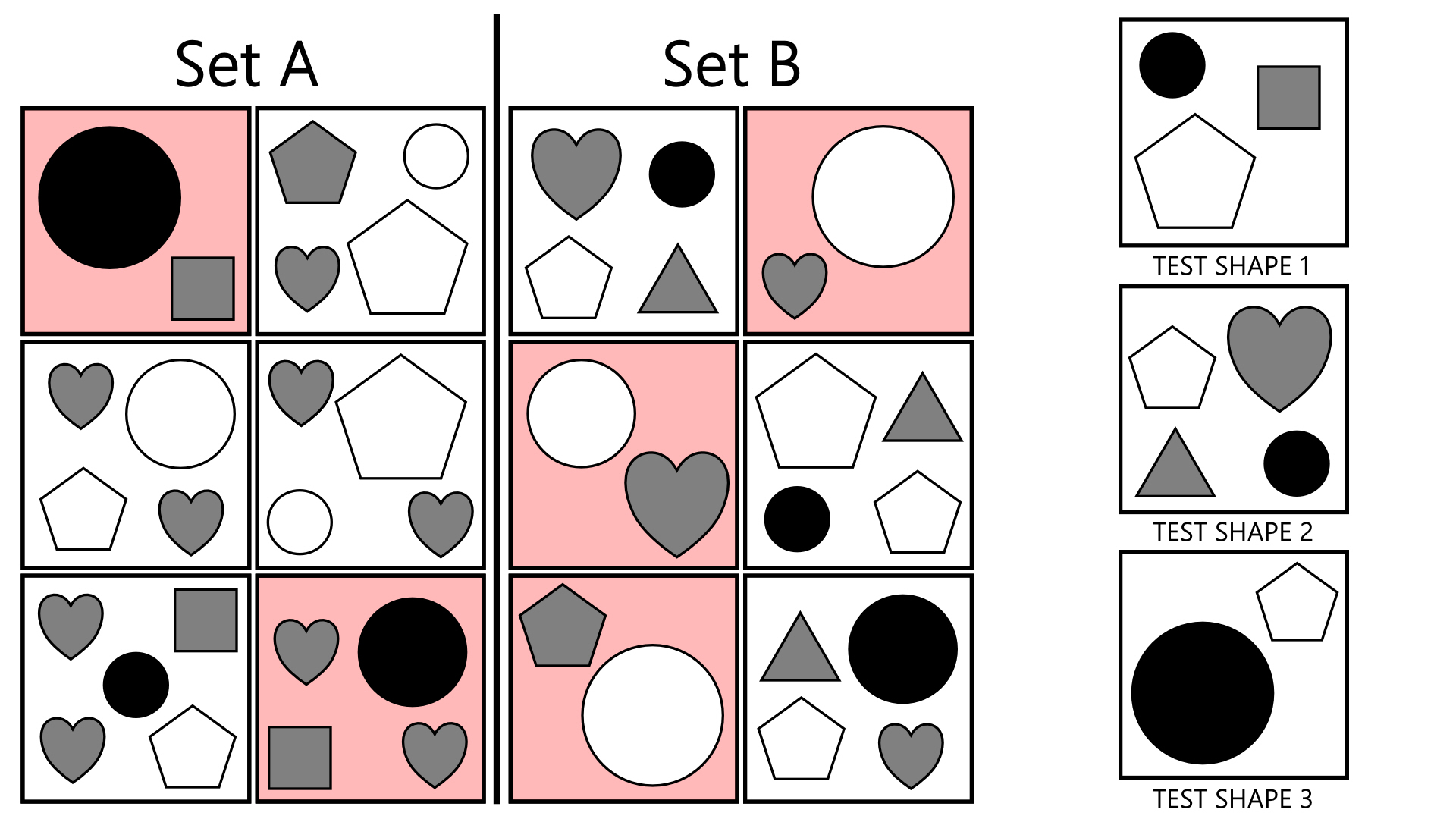

UKCAT Abstract Reasoning Simplest Squares Method

The Abstract Reasoning subtest is commonly the most feared by prospective medical students, and for good reason. While the other sections involve skills that are familiar to candidates, such as verbal comprehension or logical problem solving, Abstract Reasoning seems completely alien and bizarre to those who see it for the first time.

It is for this reason that practice is absolutely crucial, as without a structured means of approaching these questions you are reduced to blind guessing under the time pressure of the exam. While in theory this would still net you 33% of the total possible marks for the section, that won’t quite be good enough to land you safely into medical school.

One of the most straightforward ways to approach the Type 1 questions wherein you are required to discern the pattern connecting all 6 boxes in Set A and B is the Simple Squares method. While you have no idea what the rules of the game are before seeing the question, you do know that there are rules, which is quite a powerful piece of information in the context of the UKCAT.

Upon seeing the six boxes that comprise Set A, simply look for the square that is the least complex, with the fewest elements. Fundamentally you know that whatever rules link the set together MUST apply to all boxes in the set, and therefore you are more likely to spot a pattern if there are fewer things to distract you. If you can identify something that connects the simplest boxes together, it is quite likely that it will link the more complicated ones too, but crucially it will take less time to form your hypothesis in a simple box.

A sample question with the 'simpler' boxes for each set highlighted in red

As seen in the example above, the squares from each set with a reduced number of elements are highlighted. The rule in this case is rather simple, in Set A the total number of sides is odd, while it is even in Set B. It’s not a difficult question, but you’re still more likely to spot the patterns if you’re mentally counting a smaller number of sides when testing your developing theories, particularly under stress.

A conditional sample question with the 'simpler' boxes for each set highlighted in red

Let’s use a more complicated example [AR-9S]. In this case, going for the simplest squares will not immediately give you the answer because it is a conditional rule. For Set A, if a square is present the circle is black, and otherwise white. Equally for Set B, if a triangle is present the circle is black and otherwise white. Conditional rules obviously require comparison of multiple squares to identify, but the method still isolates important components. For instance in the first square of Set A, you know that either the circle, the square, or their properties must be important, or indeed the lack of the other shapes there. That starting point should lead to the realisation that the colour of the circle is dependent on the square.

I hope you found this article useful for your UKCAT preparation - if you did be sure to let me know via the contact form!

Interview Question: Organ Transplant Dilemma

Suppose you’re a surgical consultant in charge of assigning organs on a transplant list, and a liver becomes available. Your hospital currently has two patients that urgently need the transplant; a 14 year old girl, and a 33 year old man with two infant children who is a regular drinker.

This is a pretty dire situation, because whatever your choice, someone is going to die and you might feel you like you have indirectly condemned them. However, without treatment, it is likely that both patients will die anyway, and therefore it is important that the chance to treat someone be seized.

The very first thing to do is work out which of the patients are a biological match for the transplanted organ. If either of them isn’t, that ends the dispute immediately. Mechanical factors could also be considered - meaning whether the size and shape of the donor liver would suit each patient and whether the procedure would be substantially more difficult in either of them, for example if one of them had hemophilia.

In the UK, only around 1% of organ donors die in circumstances where their organs can be safely donated to another person.

There are then an enormous number of circumstantial factors that could then be assessed. For example, the father patient has a history of drinking, although the question does not say to excess. Might the teenage girl be more responsible with the liver and avoid heavy drinking? Demonstrate to the interviewer that you are aware that many of these social elements can be important in making the choice.

Perhaps the most important concept is that of Quality of Life (QoL). Which of the patients stands to gain the most with regards to long-term prognosis as a result of the transplant procedure? This is difficult to measure, but the Quality-adjusted Life Year is the most commonly used method. Essentially you’d wish to know which patient would live the largest number of years with the highest level of health - the girl has longer to potentially live, but would this necessarily be in the same health state as the father if something went awry during the operation?

Is it right that a heavy drinker should get a liver transplant over a non-drinker? These questions are very important for systems with constrained resources such as the NHS.

You may also consider the social impacts of your choice. The parents of the teenager are likely to suffer very badly emotionally if she were to die, due to her not having lived a full life, which would seem a great injustice. Conversely, the QoL for the two infant children would also likely be negatively affected by the lack of their father if he were to die.

Your interviewers will not expect you to choose ‘the right answer’ in these scenarios, as very often (if not always) the questions are designed such that one does not exist. Avoid jumping to a conclusion very quickly, as it’s all about how carefully you can assess the situation and consider as many factors as possible. Do choose an answer and provide solid reasoning to back it up, but always communicate that there are valid arguments on both sides.

Interview Question: Consequences of an Ageing Population

Medical advances inevitably result in citizens living longer lives, which we can all agree is basically a good thing. However, this results in a population that is not only larger overall, but also older on average. This change presents its own particular challenges for many aspects of society in the UK, including employment, economics and of course, healthcare. As of 2011, 16.4% of the population was aged 65+, but this value is increasing all the time. It is estimated that by 2039, 1 in 12 people will be older than 80!

Older patients have a much higher frequency of certain chronic conditions than average, such as heart disease and atrial fibrillation (irregular heartbeat). This will require more support staffing in these areas, which may divert funds away from other departments if the budget cannot be increased.

Another obvious factor is that of frailty - older individuals can typically not move around as easily, and may be at greater risk of damage from common injuries such as collisions and falls. They also are more likely to need longer periods in hospital or in care elsewhere, as well as provision of mobility aids (wheelchairs, scooters and the like) and in-home care or social workers.

Medical care is extending lifespans further and further, with ever-increasing costs

Furthermore, as older patients are more likely to suffer from multiple concurrent illnesses, this can often make their healthcare needs more complex, which in turn increases pressure on multiple NHS departments to meet with the patient and communicate between themselves. Additionally, this means longer stays in hospital which reduces the number of beds available for other patients, which is one of the most common causes of delays in treatment.

This all means that in a time of intense budget cuts and staff shortages, NHS services can become very stretched, particularly during the winter. This is true both of ambulance services and GP offices - three out of ten ambulance trusts in England declared a critical situation in the winter of 2014.

3 of 10 English ambulance trusts declared a critical situation in 2014.

Certain steps could be taken to mitigate the effects of the aging population, which mostly centre around lifestyle changes. The UK government published the public health ‘White Paper’ in 2004 which aimed to improve public awareness of these changes, which include healthy eating and physical exercise every day. Additionally smoking was banned in all workplaces in 2007.

These changes aim to improve the health of every member of society such that chronic conditions such as diabetes and heart disease are less prevalent, and prevent them from acting as such a large drain on NHS resources in order that better healthcare can be provided for everyone. This way the problems can be reduced in advance rather than than requiring very expensive treatment later on.

Interview Question: Sharing Exam Information

You are a second year medical student and have just finished your final exam of the term. On your way out of the venue, you hear several classmates talking and it becomes clear that they are writing down the questions and answers to give to the students taking the exam next year. What do you do?

This is a question that above all things tests integrity. There are many good responses that candidates could provide, but here are a few example talking points to make sure you’re covering a few bases in the interview.

Firstly, speaking to the friends in confidence first is always a good starting point. Their intentions seem to be good in helping their fellow medical students, but of course sharing the information with other students is cheating. Of course speaking pragmatically, they might feel like they were reducing the stress of younger students and therefore doing a positive thing.

Exams are there for a reason, and in medicine they're important for patient safety

However, it interferes with the examination process which is not only dishonest, but medical exams are intended to prepare doctors for practice and exposure to the public. Cheating might leave gaps in crucial areas of knowledge which the exams were supposed to identify. Furthermore, if a large number of students gets all the answers right in the next year, then disciplinary action could be taken against your friends if the academic staff found out what had happened.

The next step might be to establish whether this type of information has been distributed amongst students before, for example to your friends by older students. If this is a problem affecting a large number of people, it warrants further investigation by academic staff.

In terms of resolving the situation, it would be ideal to recommend that your friends do not go ahead with sharing the exam information and give them the chance to do so. If that doesn’t seem likely, at that point it would be worth discussing in private with your tutor before taking further action.

Fairly obviously, don’t agree with the friends and don’t offer to help them.

5 Tips for UKCAT Test Day

Okay, this will be a simple one. You’ve read through all my resources, studied hard, practiced as much as you can and it’s the night before UKCAT test day. Put the books away, unwind and check out these final tips to make the experience go more smoothly.

1. Get a good night’s sleep

It’s simple but good advice - as much as some of us (myself very much included) don’t like to admit it, you won’t perform at your very best if you’re tired and irritable. The stress of taking the exam is enough, and you don’t want to add to it by making silly mistakes and losing focus. Eliminate all light and noise from your room, and if that means using a sleep mask, earplugs and the like, so be it.

Get plenty of shuteye the night before so you can perform at your best

2. Get there early

Ideally, go to the test centre a few days (or more) before your test to make sure you know exactly where it is and how to get inside. I assumed that I’d be able to rely on GPS to get me there, which turned out not to be the case as my mobile data promptly ran out more than 10 minutes away from the centre. Thankfully the strangers of Newcastle-upon-Tyne were friendly and accommodating as they so often are to bleary-eyed students in the mornings, but the added anxiety of having to find the damned place was not something I needed.

3. Don’t cram in the morning

Some of you will be very tempted to do this, but I really wouldn’t bother. The UKCAT measures attributes that are much better honed over weeks than days or hours, as it’s more about being used to the type of question you might be asked rather than the content. To reiterate, it’s about HOW you approach the test rather than short-term memory games for the most part, where elements such as time management and triage become much more important. Cramming in the morning is very unlikely to help you, go in with a clear head and just do your best.

No cramming! - it won't help you and you might as well be relaxing

4. Do not panic during the test

Again, this might seem obvious but it’s worth thinking about. The UKCAT, as with the BMAT is very time-intensive by design, so getting worked up during the test could cost the few precious seconds it takes to answer another question. I strongly recommend reading up on a few breathing exercises, such as the 4-7-8 method (in for four seconds, hold for seven and exhale for eight). I found myself with a tiny smidgeon of time to spare after the first section during my test, and getting my heart rate under control before the next started made me feel much calmer and more in control.

5. When it’s over, it’s over

One of the small reprieves of the UKCAT is that you get your result immediately upon finishing it, which removes the trepidation of a marking period. You may only take the UKCAT once during each application cycle, so take your mark and be proud of it, knowing that you did your best. Instead of fretting over small mistakes you think you might have made, now you should be looking ahead, thinking of the best places to apply with that score - research average cutoff scores for different schools, as well as graduate entry courses if applicable to you.

With all that said, just try to do your best. Everyone is just as stressed as you are about this, but remember what it’s all about - just one of the many hoops you’ll need to jump through to achieve that goal of becoming one of the UK’s best and brightest young doctors.

Be sure, if you haven’t already, to look at my other UKCAT preparation articles and I’m always happy to answer any questions you might have via the contact form.

Good luck!

Interview Question: Lost Blood Sample

Imagine that you’re a medical student on placement or junior doctor on a hospital ward. A patient’s blood sample has gone missing, and you need to explain to them that another one needs to be taken.

It doesn’t have to be blood - it could be stool, urine or some other bodily substance of your choice. This is a common type of question, which combines a number of issues. The best way to approach these scenarios is to consider what the patient might see from their point of view when faced with this scenario.

Firstly, the concept of their privacy. Blood bottles can feature a patient’s first name and surname, their ward, their date of birth and more besides. At the very least, this information is now in the open, and potentially visible to anybody else on the ward, including other medical staff, patients and even visitors. Because this information is supposed to remain entirely confidential, the patient might think that a breach of trust has occurred.

Secondly, having a blood sample taken is not a comfortable procedure at the best of times for many people, particularly if multiple attempts were needed. Because of a hospital mistake, they have to undergo this pain again.

Blood sample being taken (Image: US Navy)

The last talking point you could consider is that of delayed test results. Because the first sample has been lost, another must be taken which involves coordinating the required staff (a doctor, nurse or phlebotomist) and sending the collected sample for testing once again. This by necessity results in the tests taking longer to come back, which may cause additional stress in patients anxious about their condition.

The key thing to remember when approaching communication, as with all answers in these scenarios, is to be completely honest. Absolutely do not use euphemisms such as ‘a small mishap’, and remember to be polite when delivering the news. You should listen very carefully to any concerns the patient has, and do your best to explain that you empathise with them.

Some stock phrases you might use for inspiration:

“Mr Johnson, I’m very sorry but there has been a mistake and your blood sample has been lost in the hospital. We need to take another from you, and I apologise that you have to go through that again during a time that must be stressful for you. We will do our very best to maintain your privacy and will get the results to you as quickly as we can.”

“I’m very sorry Mrs Lindham, we don’t know the whereabouts of the blood sample that was taken from you yesterday. In order to get your results back to you quickly we need to take another one. I completely understand if this frustrates you and I’m deeply sorry for what has happened, but we want to do the best we can for you moving forward. Please let me know if you have any concerns.”

Simply put, own the mistake, be courteous and deliver the news in as straightforward a manner as you can. The patient has every right to be irritated or upset, so hear them out and make sure they know that you have taken their views on board. They must be absolutely clear on what exactly has happened, why it has happened, and what the next steps are.

The Charlie Gard Case

Medical cases are often matters of life and death by definition, and cases involving children can become incredibly emotionally charged. Because of this, multiple media sources have pounced on the recent incident involving the young Charlie Gard at Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH), and much misinformation has been been distributed by the public as a result. The following is my attempt at clarifying the issue as much as possible from a purely objective standpoint for those interested in the case.

To begin with, what does Charlie have? At 10 months old, he is suffering from infantile onset encephalomyopathic mitochondrial DNA depletion syndrome (MDDS). It is key to note that this describes a group of diseases, which result from different genes becoming mutated, so Charlie has one particular variant. In his case, he has two mutant versions of the gene coding for the RRM2B protein, a ribonucleotide reductase enzyme required for the synthesis of DNA in his mitochondria - the ‘powerhouses of the cell’ if you recall your biology classes at school.

These mutations resulted in Charlie experiencing encephalopathy (a loose term for ‘brain disorder’), organ failure and muscle weakness, which affects his ability to breathe. It should also be noted that while cases of MDDS are very rare, there are multiple instances of Charlie’s variant known to medical science. As of writing, no treatments for any variant of MDDS have left the medical trial stage, and none of these have ever been tried on a patient with the RRM2B variant that Charlie has.

Charlie was initially brought to a GP because he was not gaining weight, and was then transferred to GOSH because of his difficulty breathing, wherein he was put on a mechanical ventilator. Following genetic screening his mutant genes were determined to be the cause of his symptoms. This occurred throughout October of 2016.

By January 2017, Charlie’s parents and his doctors had concluded that an experimental nucleoside therapy was the best treatment available. This treatment would deliver Charlie nucleosides, which are the precursors required to build DNA that his mitochondria cannot make for themselves. Ethical approval was compulsory for this treatment to go ahead, but Charlie had severe seizures while this was being sought. The doctors decided that because it was likely that Charlie would develop further brain damage after these, and at this point concluded that the experimental therapy would not improve his quality of life. At this point, the medical team began to discuss end-of-life care with Charlie’s parents and the idea of withdrawing life support so as not to prolong his suffering.

Charlie’s parents launched a GoFundMe campaign at the end of January, with a goal of £1.2 million to cover the costs of an experiment US treatment. By April this goal was reached, and after three months the total amount reached more than £1.3 million.

By 24th February 2017, GOSH applied to remove Charlie’s ventilation apparatus, which the parents challenged. This went to High Court, where Charlie’s interests were represented by an independent advocate appointed by the court. Justice Francis ruled that due to the very low chance of success in the therapy and the risk that Charlie was experiencing pain, the ventilator should be withdrawn. The US doctor who would provide the treatment said it was ‘very unlikely he (Charlie) would improve’. The proposed treatment had never been used in patients with the RRM2B MDDS variant Charlie has, and the treatment itself had received no published case studies at all, or indeed been used in patients with encephalopathy.

Charlie’s parents then took the case to the Court of Appeal, which refused to overturn the previous decision. The Supreme Court then followed suit, saying that there was no arguable point of law. His parents then appealed to the European Court of Human Rights, which was also rejected. Finally, they made the claim that they had wanted to bring Charlie home or to a hospice to die, but the hospital had not allowed them to do this. The hospital would not comment due to patient confidentiality, and this claim has not been independently verified as of writing.

It was decided that Charlie’s life support would be withdrawn on 30th June, at which point GOSH agreed to give his parents more time with him. A week later, GOSH took the case back to High Court, citing ‘claims of new evidence relating to potential treatment’. It was during this next hearing that the US doctor, Michio Hirano agreed to be publically identified, and Justice Francis ruled that he should be allowed to examine Charlie and speak to GOSH staff, after which Hirano would bring his report back to the court. During these first two weeks of July, the much-publicised offers for help from both the Vatican and US President Donald Trump were received.

Following this process, Hirano concluded after visiting Charlie that he saw no chance of the treatment working at all due to the extensive irreversible brain damage he had already suffered. He therefore withdrew his offer to perform the treatment, and Grant Armstrong QC, the barrister representing Charlie’s parents withdrew their challenge against the removal of Charlie’s ventilator. The prime goals of each party were as follows: Charlie’s parents wished to exhaust all possible options, so that any opportunity that might help Charlie had been taken, while Katie Gollop QC stated on behalf of GOSH that their view was the nucleoside treatment, if it worked at all, would leave him with no quality of life whatsoever.

Because of his condition, it is not possible to know whether Charlie was experiencing pain. He is deaf, blind, mute, and is incapable of movement. As of writing (24th July 2017) Charlie Gard will receive palliative care at GOSH and will die in hospital.

Top 5 Tips for BMAT Success

Most people who apply to medicine will take the UKCAT entrance exam, particularly if transitioning to a medical degree from A levels. If you want to go to a few specific schools including Leeds and Oxford, you'll take the BMAT instead - graduate applicants might see it used in lieu of the UKCAT for some universities too, depending on the institution. Here's my 5 tips for BMAT success.

1. Do it a year in advance

I wanted to get this one out of the way early, because it won’t be applicable to many of you. But if you get the opportunity, book yourself in for the BMAT a year early and get some experience of having taken it. It doesn’t matter at all how you do, but when you leave you can write down everything you remember about how you felt, how you managed each section and you’ll be much more prepared in that sense than someone who’s taken it blind, which could remove some anxiety when test day comes around.

2. Own Your Weaknesses and Tackle Them Early

Unlike the UKCAT, the BMAT actually tests many principles of scientific understanding, which can be drawn from Biology, Chemistry, Physics and Mathematics, to GCSE standard. Do as many practice questions as you can and establish what your weakest sections are first, so you know where to apply your focus. In my case, studying a biology degree, there was little sense in revising GCSE biology, but it turned out I had forgotten some core principles of chemistry. Use this more methodological approach which will save you time and money when purchasing revision aids.

The time pressure is the major difficult element of the BMAT, perhaps even more so than the UKCAT

3. Practice for time pressure